- Main problems in creating think tanks in Turkey (1) (2), Hasan Kanbolat

- How Do We Affect The Image Of Armenians In Our Communities, Kay Mouradian

(Any Pointers To Be Applied To Turks Abroad?) - Rhetoric And Reality: Turkish Politics Inside And Out, Nigar Goksel

- We Respect Your Otherness As Long As You Are Not The Other, Burak Bekdil

- Sometimes it’s better late than early!, Burak Bekdil

- Ugly Truth About Kurdish Question -- Armenian Question!?, Orhan Kemal Cengiz

- Istanbul Diplomacy*, Kerim Balci

- Standing Up To Barack And Company: Armenia, 3m Realpolitik And Integrity Thing, Raffi K. * Hovannisian * Armenia's First FA Minister

- Conscious Existence? What Does it Mean To Be Armenian?, Seda Grigoryan

- Why Don't Jews Condemn Anti-Semitism In Turkey?, Harut Sassounian

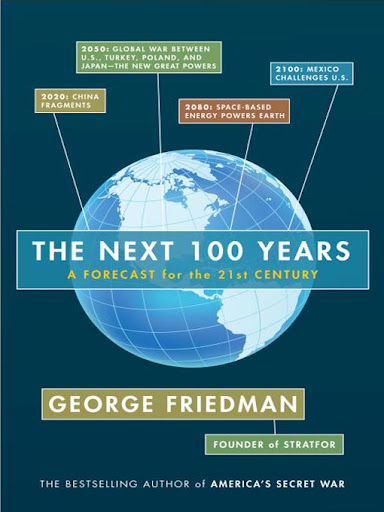

- 'Next 100 Years' May Not Bode Well For Armenia, Andy Turpin

- History, Used And Abused, Chris Patten*

- Wake Up, Armenians!, IDHR

- Solution To Nagorno-Karabakh: Always Around Corner, Amanda Akçakoca

- Peace Process: Where We Are Now: Summary Of Progress On Road To Settlement, Kenan Guluzade IWPR

- With Or Without Turkey, That Is The Question, Defne Gürsoy

- Pierre Lellouche: “Turkey’s Lawyer” Or “Sarkozy’s Trojan Horse”?, Mehmet Ozcan, Head Of EU Studies, USAK

- Why We Should Read `History Of The Armenians', Eddie Arnavoudian

- Please Tell Us The Truth, Odette Bazil

- Jews of Turkey and Armenian Genocide, Jean Eckian

- Deadlock Or Delay: Negotiation Process On Karabakh Issue Is Taking A Break For Indefinite Time, Analysis: Aris Ghazinyan

Main problems in creating think tanks in Turkey (1) (2), Hasan Kanbolat @Todayszaman.Com

In Yaşar Kemal's novel “İnce Memed” (Memed, My Hawk), one of the characters, Topal Ali (Lame Ali), is known for his skills in tracking people. After Hatçe, the girl Memed loves, becomes engaged to another man, Memed abducts the girl and brings her to the Toros Mountains.

Topal Ali is charged with tracking down the two lovers. “If he wants, although there is no rain, he tracks dry soil, rocks and even birds… As long as a part of its wing touches the soil even a little bit. Especially humans! He can smell humans even if they had passed by the road three days ago.” The villagers beg Topal Ali not to find clues leading to the lovers and to pity them. Ali feels pressure from hundreds of villagers and decides to pretend not to find traces of the lovers. However, one of the villagers, Kel Ali (Bald Ali), explains Topal Ali's weakness when it comes to tracking people: “Topal follows the clues of even his father. Even when he knows that they will hang his father when he finds him, he cannot help but track his father. He is a good, nice man, and he feels sorry for the lovers, yet he cannot help tracking them. Nothing can prevent him when it comes to tracking. Even when he knows that he will be killed and he will eventually see death, give him a clue and he will follow it.” Starting to track İnce Memed and his darling, Topal Ali does not want to find clues. He knows that once he begins to track people, he cannot help but find them. However, he still cannot help it. He starts following the clues. The clues lead him to where the two lovers hide. While Topal Ali is glad to find the clues, he feels deep sorrow for catching the lovers.

Is a strategist a “Topal Ali”? Would his experiences, skills and tracking abilities encourage him to follow the clues to the end even if the issue would harm him/her eventually? Kemal presents tracker Topal Ali to the readers in his novel of “Memed, My Hawk.” A strategist is a person who leaves his feelings and political views to one side and evaluates things in an impartial way. Tracker Topal Ali is also a strategist in a sense. Following clues like a strategist, Ali collects new data, evaluates them and analyzes them using his experience and knowledge. A strategist is successful if s/he is rational. At the same time, strategy is a natural skill like math, music and sports, and it is also a lifestyle shaped by skill. If this natural skill is developed, genius can be achieved. Other than discovering something new, it is also important to be able to see incidents from different perspectives.

In Turkey, industry is transitioning from labor-intensive sectors to technology-intensive sectors. In the new world, where raw information grows, mobility increases and time becomes more and more important, the need to analyze gradually increases. For this reason, think tanks, which are institutions where data are processed and analyzed, gain importance. Foreign policy actors as well as the process of creating new foreign policies have transformed. Think tanks can take their place in international platforms where the state cannot enter. Forming a foreign policy for Turkey in cooperation with think tanks and informing think tanks about foreign policy are in Turkey's interests.

The war in South Ossetia (Aug. 8-12, 2008) proved the importance of think tanks for Turkey's foreign policy. The war indicated that Turkish think tanks, which have almost a decade of history, will begin to have an important place in Turkey's foreign policy. Turkish think tanks informed the public, made analyses and published reports during the war. The same sensitivity, the same speed of making decisions and the same kind of analyses would not have occurred in state offices, in political parties and in Parliament. Just as the US entering Iraq showed the importance of news stations that presented viewers with a 24-hour live broadcast of the situation, the war in South Ossetia proved the importance of think tanks in Turkey.

In Turkey, working at think tanks or policy institutes is not a profession where you can invest in your career. This profession, which can have the title of strategist, analyst, political analyst, foreign policy expert, foreign policy researcher, think tank expert or think tanker, is not regarded a full-time profession. It is a profession that has not evolved into a career, which is not defined and which does not have a unique name. Time spent at think tanks is regarded as time wasted. For full-time strategists, time spent at think tanks is destined to fade away like writing on the surface of a lake. It is known as a full-time job for retired high-ranking bureaucrats and postgraduate students and as a part-time job for academics.

Those who complete their doctoral theses while working at Turkish think tanks tend to move on to work as lecturers at universities. Since working as an academic gives one a good career-track job, is easier to do and provides shelter against fears of unemployment, young strategists opt to shift toward the academic world after completing their doctorate. On the other hand, movement from the academic world to think tanks is generally toward executive positions. Still, these movements generally occur for a temporary period of time -- for several years at most. Movements from the civilian or military bureaucracy are generally seen in the form of resignations from previous jobs. High-ranking retired civilian or military bureaucrats tend to consider think tanks simply a good alternative to staying at home and as a potential means of entry into active politics. Furthermore, there are analysts in pajamas who stay at home and write amateurish articles as strategists in their retirement.

The biggest challenge for think tanks in Turkey is attracting well-educated experts (aged between 25 and 55) for an extended period of employment. For think tanks to have a bright future, they should be able to offer long-term contracts and long-term employment guarantees to strategists who can turn think tanks into career centers and ensure mobility. In the 1950s, Sait Faik Abasıyanık applied to the police department to obtain a passport. He wrote "author" in the profession box on the application form, but the police officer in charge told him that there was no profession defined as "author." So he had to change it to "unemployed." Until the 1950s, being an author was not considered a profession, and 50 years later, now, being a strategist, which is a profession of intellectuals, is not regarded as a profession. Being a strategist must be made into a profession that is formally recognized by the general public and the public and private sectors.

In Western countries, think tanks and strategists are part of the system. Think tanks are the workshops where policies are tailored. Their clients are the decision makers. For this reason, there is a high rate of mobility between think tanks and the public sector, the media, universities, the private sector and politics in the West, particularly in the US. However, in Turkey, think tanks are not part of the system although they are close to decision makers. The rate of mobility between think tanks and the public and private sectors is very low. The only sizable mobility exists with the academic world and the media.

In the West, particularly in the US, the public and private sectors have the tradition of assigning projects to think tanks. In Turkey, on the contrary, the public and private sectors do not have such an institutionalized tradition. Moreover, in Turkey, plagiarism is comparatively widespread and considered normal, which makes the survival of think tanks very hard.

Turkish think tanks are further handicapped by the challenges of securing reliable financing, recruiting a permanent staff, ensuring harmony among the staff, using time in an efficient manner and obtaining up-to-date information. In Turkey, strategists have mobility with universities while their mobility with bureaucracy and politics is limited. The existing system in the public and private sectors and in universities is miles away from properly supporting think tanks and encouraging young people to specialize in foreign policy areas. Turkish think tanks are not able to utilize the public sector's sources of information in the public domain. In Turkey, the public sector has a monopoly over crude information in the foreign policy and security fields. There is virtually no public organization from which one can obtain information concerning foreign policy matters. In regions of interest, Turkish think tank officers open offices. The realities of these regions, maybe even the languages spoken ,are not fully known.

In Turkey, the rate of turnover of employment is very high at nongovernmental organizations and think tanks. This leads to a weaker corporate identity.

02.08.2009, Zaman

How Do We Affect The Image Of Armenians In Our Communities

(Any Pointers To Be Applied To Turks Abroad?)

By Kay Mouradian, EdD Humor and suffering are often two sides of the same coin and successful comedians understand that nugget of truth and utilize humor to lighten suffering. Shock jock Bill Handel of KFI and his cohorts in their unattractive attempt to be humorous about reducing the U.S. population to save the government money proposed to clean out Glendale and its Armenian population with a racist comment, "What the Turks started, Bill will finish."

Would they have had the audacity or courage to say, "Let's clean out Beverly Hills of all its Jews and finish what Hitler started!" We all know that would never happen, because Jews all over the world would react furiously, call Handel anti-semetic and become successful in having him fired immediately.

Then the question becomes why would Bill Handel never think about such an antipathetic statement about the Jews? More than likely it's because he's been educated to understand the magnitude of suffering from the Jewish Holocaust. And why does he have such a lack of awareness about the Armenian Genocide and the depth of cruelty and suffering imposed upon the Ottoman Armenians? How many books about the Armenian Genocide are in print in comparison to the more than 50,000 books written about the Jewish Holocaust? What does this say about our community, our writers, and the images we would like to portray?

And how do you personally affect the image of Armenians in our community? How many of you reacted with potency to the outrageous rant of Bill Handel? How many of you reacted to KCET on April 24 when our most popular public television station did not show any Armenian genocide documentaries?

What I see is apathy from our community and I feel that education is the key to promoting understanding. If we expect non-Armenians to care about us they need to understand where we came from, the effects of the Armenian genocide on the Diaspora, how difficult it was for our people to leave their homeland, in some cases two homelands, and give up their livelihoods to start all over again in a foreign country. I applaud those who survived, I applaud those who came to America with nothing, worked hard and educated their children, and I applaud those who tell our story to those who do not know and through those stories project the dignity of truth. It is our responsibility to history.

Kay Mouradian, EdD is author of A GIFT IN THE SUNLIGHT: An Armenian Story

Any Pointers For Turks ?

Rhetoric And Reality: Turkish Politics Inside And Out, By Nigar Goksel *

— Turkey sets high expectations with rhetoric about its indispensable role for the solution of regional conflicts, for bridging civilizations, and for spreading values of tolerance and democracy among its neighbors.

However, Turkey itself is polarized, ridden with cultural clashes, tolerance deficits, and widespread conviction that domestic balances of power are inadequate. And it is not only the domestic environment but also perceived dissonance in Turkish foreign policy that raises questions about Turkey’s ability to maneuver the complex dynamics of its neighborhood.

Turkey’s added value

The debate about Turkey’s foreign policy in Washington centers around whether Turkey is anchored to the West as it strengthens its regional ties or whether Turkey is intent on creating a second bloc, a “Muslim pole,” for a new and just world order. In other words, does Turkey aim to leverage its indispensability toward being a full and equal partner of the Western bloc, or is Turkey positioning itself as a stand-alone power that has to be reckoned with for policy accomplishments in this region?

In terms of anchoring Turkey in the West (and vice versa), a promising step took place on July 13 with transit countries signing an agreement on the strategic Nabucco pipeline, set to bring natural gas from the Caspian to Turkey and onwards to Europe. At the time, this author was in Baku facing questions from Azerbaijani oppositionists on why the Turkish government can confront Israel over the Palestinians and China over the Uigurs, but remain silent as youth activists face violence and are imprisoned in Azerbaijan.

Energy deals between Turkey and Azerbaijan, alongside rhetoric of brotherhood between the nations, does not meet their expectations. However, there are no easy answers to the challenges of Turkey’s neighborhood, and leaving questions hanging is a tactic used all too frequently by Ankara. Asked by some in Washington, “If Turkish foreign policy is all about realpolitik, why does the Prime Minister seem to be trying to win the Arab street when it comes to Middle East policies, even when this means alienating key Arab regimes?” Lala Shovket Hajiyeva, the head of a small opposition party in Azerbaijan, echoes a common sentiment among the vocal opposition when she says, “I wish it was Turkey and not the Europeans bringing us democracy.” A young activist noted that the frustrations in his country, coupled with schools and networks allegedly connected to the Fethullah Gülen movement, gradually lay the foundation for a religiously-motivated political alternative in Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, the country’s ruling establishment performs a challenging balancing act between not only the West and Russia, but also the interest-driven power centers within, as well as expectations within society, that have grown by witnessing domestic changes in neighboring Georgia that have improved many aspects of Georgians’ lives. Commenting on Turkey’s influence in Azerbaijan, a more cynical (and older) Azerbaijani simply said, “just make sure to move Turkey forward to the EU because if you head anywhere else, it will affect our direction ever more.”

Turkey as a center of attraction

Today, Turkey is ever more polarized. Clashing camps speak of the “greater good” of their cause. A member of the government may claim that a de facto affirmative action-like approach is legitimate, in order to empower the conservative classes that have been excluded for decades. On the other hand, many staunch critics of the government perceive state capture and power abuse by the ruling party and fear this will become irreversible due to a weak balance of powers.

The shortcuts to identifying who belongs to each camp get shorter by the day, including the newspaper one reads, the TV channel a company advertisement is broadcasted, and even the restaurant that slips a person’s name to the front of the waiting list. Express concern of patronage in an AKP municipality and someone is coined a “Kemalist.” Mention the harm of banning headscarves in universities and one is labeled an opportunist who must be trying to appease the government, if not an outright Islamist. There is a divided judiciary, parallel lawyers associations, bureaucrats pitted against each other, and battling nongovernmental organizations. Turks might get shuffled into a camp to which they do not feel affinity, based on shortcuts for classifying people based on symbols.

Foreigners are not immune from this absurd reductionism either. After four Azerbaijani members of Parliament visited Turkey and criticized the government for their Armenia policies in April, the Turkish Prime Minister reportedly accused them of being connected to Turkey’s deep state. There have indeed been attempts to wrestle power from this government using undemocratic means, with many of the involved currently on trial or being investigated. However, exploiting this by labeling critics of the government as coup-mongers is unjustified. Tolerance to criticism on behalf of the government in Turkey would be most inspiring to those from countries where aligning with power holders is necessary for social and economic mobility.

International expectations of courage and vision from both Turkey and the current U.S. administration are enormous. While the U.S. administration is mirroring its policy of “reaching out” in the world with its domestic efforts to do so, the Turkish government must also go out of its way to overcome traditional lines of confrontation with its legitimate critics in Turkey itself. This will be what determines its success both domestically and globally. A good place to start in building confidence inside would be to move forward with reforms foreseen in the European integration agenda that also curb the power of the government.

The United States, the European Union, and Turkey

Within Washington the debate about Turkey is weak and divided. While some in the U.S. capital noted the rapid extension of congratulations from Turkey to Ahmadinejad after the elections in Iran as an extension of Turkey’s realist and pragmatic foreign policy, others saw this as a sign that power would eventually be consolidated by Islamists in Turkey while Iran joined the free world.

In a sense, the Turkish government has a stronger hand in its relations with Washington than ever before. The Obama administration is attempting to reach out to the Muslim world and a conservative Muslim party with strong popular backing is governing Turkey. In negotiating with the United States, AKP can conveniently point to the still very high levels of anti-Americanism in Turkish society as a bargaining chip. The leading opposition parties are all more U.S.-skeptic in rhetoric than AKP. Moreover, with many more pressing challenges on its agenda, Washington would hardly opt for more strain in its Turkey ties.

During the Cold War it was important for the Western alliance not to “lose” Turkey, and it is today too. However, today when the risks of losing Turkey are debated, it is the value of Turkey’s soft power that is in the forefront, not its geostrategic and military function. Faced with a new set of regional challenges and very different power balances in Turkey, it is the ruling AKP with which Washington needs collaboration most. It is often said that Washington turned a blind eye to abuses committed by the Turkish military when the military relationship was central to the two countries’ joint interests. It is important today that expectations from the Turkish government regarding rule of law and pluralism are not lowered.

Ranging from impartiality of the judiciary to institutional arrangements to combat corruption, the EU membership requirements address the many issues that are critical for Turkey to implement in order to break out of the nearly chronic perception of existential crisis. It is, therefore, puzzling that the Turkish opposition parties are not calling for the EU accession agenda to be implemented more aggressively in Turkey. Those in both Turkey and the United States who are concerned about Turkey’s direction should put more emphasis on the roadmap that the EU process provides.

The messages President Barack Obama gave during his recent visit to Turkey reflected a welcome sensitivity to Turkey’s internal balances by emphasizing principles over partisanship. Though it is in the interest of the United States that Turkish democracy is consolidated, Washington has a limited set of tools to steer Turkey down this path. The EU process is the single most influential factor in correcting the many distortions within Turkey’s political world. In this sense, disheartening messages from European capitals about Turkey’s eventual membership strike a blow not only to Democrats in Turkey but also to the strategic interests of Washington.

»» The German Marshall Fund Of The United States On Turkey

* Nigar Goksel is a senior analyst at the European Stability Initiative and editor-in-chief of Turkish Policy Quarterly. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of GMF or those of the European Stability Initiative.

31 July 2009, Zaman, * Nigar Goksel The German Marshall Fund Of The United States

We Respect Your Otherness As Long As You Are Not The Other, July 31, 2009, Burak Bekdil

It is very kosher, according to endless statements reflecting the pragmatic selves of our leaders. Not very much so, according to endless behavior reflecting their Islamist selves. Seven years of Islamic rule must have taught any journalist, except for the ‘missionaries,’ not to be appalled if Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan accused a certain ethnicity of “knowing how to kill,” or another of “near genocide,” all depending on Mr. Erdoğan’s heart-felt sentiments about ‘the other’ in a religious connotation.

It’s like a journalistic reflex, if you happen to be in this trade in Turkey, not to raise an eyebrow to a news headline that might tell you “motorbike crashes into car, four dead.” You must learn not to be curious at such bizarreness and automatically assume that half a dozen people must have been riding the ill-fated motorbike when the accident happened. Actually, this is precisely what happened a few days ago: Four dead and four wounded, when a motorbike with five people riding together crashed into a car.

I was therefore perplexed when our colleagues were perplexed because a fiercely pro-Erdoğan columnist recently complained that “the Alevites unfairly occupied too many bureaucratic seats in proportion to their ‘size.’” What kind of a sect is this, inquired the columnist in support of the Sunni elite he probably hoped to impress. But that, too, should be all too normal in a land where talk of multiculturalism is a great thing, but its practice is a rare commodity.

What should we understand of multiculturalism? Political views have been diverse. According to Voltaire, “If there were only one religion in England there would be danger of despotism, if there were two, they would cut each other's throats, but there are thirty, and they live in peace and happiness.”

But according to Vaclav Klaus, former president of the Czech Republic, “Multiculturalism is a tragic mistake of the current Western civilization for which we all pay dearly.”

In the land of the Crescent and Star, President Abdullah Gül told an audience recently that “our differences are our richness” in what was apparently a direct reference to Turkey’s Kurds. No doubt, this would be a beautiful sentence in any language, but anyone who knows a little history cannot help to ask if our differences are a point of divergence generating cleavages that might even lead to civil wars, or are they really our wealth which might help to build a stronger national unity? Of course, we all can take what we want from this sentimentally optimistic sentence, but ideally what we ‘say’ should be at least not too different from what we ‘do.’

Sadly, we are always very good at rhetoric, and not so good in action. Was it not Mr. Erdoğan who, in another beautiful sentence, said that it was wrong to judge people by how they look? But, yes, that was a reference to secularist discrimination against women who wear the Islamic turban. Turban or no turban, Mr. Erdoğan was right – in words. What about a little bit of consistency, for God’s sake?

A recent story tells us not to rush to premature optimism of anyone’s fancy lines. As the prime minister was being driven in a motorcade, according to various accounts, he noticed a group of rockers queuing up for a concert. Here comes the controversial part. According to the official account, these rockers protested Mr. Erdoğan with insults (described as ‘rockers’ salute’); but according to the protestors, that was just a peaceful protest. But we certainly know that whatever method the protestors may have chosen, it was not violent.

The rest of the story hardly complies with Mr. Erdoğan’s rhetoric and preaching that “we should not judge people by their looks.” An angry Mr. Erdoğan took the platform shortly after the incident and complained about “youths being degenerated/demoralized.”

So was that not ‘judging people by their looks?’ What about the sacred right to protest? How does Mr. Erdoğan know that a young man dressed differently from a ‘good Muslim’ and protests the prime minister is a degenerated young man?

The protestors were immediately detained and ‘thoroughly’ questioned by the police. The interrogation included McCarthyist questions like “Which party did you vote in last elections?” and “Did you show up at the republican (anti-government) protests (in 2007)?”

Perhaps Mr. Erdoğan, the ‘good Muslim,’ should learn more about Islam. He can always start re-reading some of the essential Koranic commandments. For instance: “O unbelievers, I serve not what you serve and you are not serving what I serve, nor am I serving what you have served, neither are you serving what I serve. To you your religion, and to me my religion!” (The Holy Koran, 109:1-6).

Sometimes It’s Better Late Than Early!, July 29, 2009, Burak Bekdil

“Affairs are easier of entrance than of exit; and it is but common prudence to see our way out before we venture in.” Thus tells an Aesop tale…

The well-known story of the Tower of Babylon (Genesis 11) talks about different people speaking the same language and coming together to build a great city with a tower to match it, but once their languages were confused as a result of a ‘holy punishment’ and they could no longer work together and the work for the great tower remained unfinished. Eventually, the ‘laborers of Babylon’ spread around the world with their separate tongues, and still to this day it is said that the problems of communication are crucial to working together and solving problems.

It has been over six years since the United States occupied Iraq, and the last couple of years have been intensely spent discussing the best ways to execute a “graceful exit”. Any sensible men, be it a planner or a foot soldier, would tell you while invasions might start with detailed military planning, they cannot end without proper political and administrative planning. The proposed U.S. exit will have several different implications across the region, and whether or not the unity of the State of Iraq will be preserved in the long-run, is for soothsayers to tell. However, what is currently taking place in northern Iraq, practically “Kurdistan,” is no doubt of great interest to the Turks.

For the U.S., the leaving and long-distance partner in the new game of exit, it is crucial that the remaining parties evolve into partners and get along peacefully to minimize the problems for Big Brother. How this relationship of hatred-to-love would be established is yet another question, with big bucks certain to play as the main lubricant. In addition, the Americans have good relations with both the Kurds and the Turks. They have provided some degree of logistical support for the Turkish war on terrorism and supported Turkish initiatives in most international forums.

The Americans have also become the hero of the Kurds, despite past heartbreaks and present suspicions for new heartbreaks, by overthrowing Saddam Hussein and generating a rather peaceful section from the remains of Iraq in its north. It is, therefore, possible that Washington can act as the go-between between the ‘bad Kurds i.e., the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or the PKK, and the Turkish government.

Washington might even be able to encourage the PKK’s military wing to surrender its arms to the U.S. military, rather than surrendering directly to the Turkish state/military. The Turkish government and the military might as well benefit from the upgraded ‘American involvement.’ In addition, all that might help remove many of the roadblocks faced by Turkish democratization efforts, which, then, would presumably help ease Turkey’s difficult march into the European Union. Going back to the trophy in the shape of banknotes, all parties involved in this foes-becoming-friends game will certainly benefit from lucrative deals, including energy, and possibly many others we cannot even imagine today.

A little more than five years ago, this column mentioned American hopes to craft a reliable alliance between the ‘only two secular Muslim peoples of the region, the Turks and the Iraqi Kurds,’ despite the tragic Turkish-Kurdish conflict in the last quarter of a century. With increasingly diverging interests, neo-cons and their often eerie ideas at the wheel in Washington, a touch of warmongering sentiment and what the Greeks would call “communication bouzouki,” the idea has failed, leaving behind many more dead men.

Now that prominent Kurds “walk like all other immortals” at international conferences as opposed to their “God-given –or simply American-inspired—mood of superiority,” the Turks, finally thinking increasingly pragmatic than vindictive, and the Americans realizing that it would not be in their best interests if more Turks and Kurds died in this already too bloody conflict, the chances for a historic –but probably temporary—Turkish-Kurdish handshake are higher than at any time since 1984.

The Kurds should come to grips with the new realities, as evidence in the election results for their regional Parliament, and recall their Turkish friends telling them not too long ago that “one day the Americans would leave and we as centuries old neighbors will have to live peacefully across a border that will either keep on bleeding or prosper.” And the Turks realize that realpolitik in the year 2009 is quite different from a decade ago when their American friends practically handed them over their most-wanted man, now in solitary confinement.

As almost always, all roads lead to Washington in this complex Middle Eastern chessboard. It will be a fine little test if the Turks and Kurds on both sides of their border had good reason to hooray when Barack Obama took over from the most-disliked U.S. president. As for the Turks and Kurds on the same side of the border, things will be a little bit more difficult, but not too difficult.

The choice is there. The Turks, Iraqi and Turkish Kurds and Americans will either speak the same language and build the Tower of Babylon in the 21st century or disperse into different tongues with the work for a great project unfinished.

The Ugly Truth About The Kurdish Question -- The Armenian Question!? By Orhan Kemal Cengiz

- If we could discuss the Armenian question openly, if we could confront the Armenian tragedy, there would not have been a Kurdish question.

We are far from understanding the Armenian question, yet can we be close to solving the Kurdish question?

To answer this, we need to look at how the Kurdish question emerged in the first place. The same state “problem solving” mentality was in work for both the Armenian and Kurdish questions. Population exchanges, forceful evacuations and atrocities directed at civilians. Nothing has changed over all these years. The same “problem solving” mentality created the very problem it was trying to solve. The Kurdish question was very simple to solve in the beginning. There was a marginal armed group (the PKK, or Kurdistan Workers' Party) which used to carry out sporadic attacks against security forces. Most Kurds did not like them. But many Kurds also wanted to be recognized as Kurds; be able to preserve and live their culture, speak their language and so on. At that time, the Turkish official stance -- dictated by the military, basically -- was very rigid on the Kurdish question. According to this “understanding,” there were no Kurds, there was no separate Kurdish language. Kurds were “mountain Turks.” They were called “Kurds” because of the sound they make when they walk on snow: “Kart,” or “Kurt.” For those of you who do not know the difference between Kurdish and Turkish, they are about as similar as Chinese and English. So basically, the official understanding of the Kurdish question was a joke. If we did not know the sufferings of Kurds as a result of this “unwise” approach, we could even say that the Turkish state has a dry sense of humor because of the creation of this “mountain Turk” concept. But it was not a joke, and this understanding of the question caused a serious human tragedy in Anatolia once again.

The treatment of Kurdish prisoners in the Diyarbakır prison after the 1980 military coup was a turning point. The torture and ill treatment of Kurdish inmates in this prison was beyond human imagination. The Diyarbakır prison was like a Nazi concentration camp. The inmates suffered so much that upon release almost all of them went to the mountains to join the ranks of the PKK. People were imprisoned even for just expressing peaceful ideas about the Kurdish problem. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the phenomenon of the Diyarbakır prison created the PKK we know today. With these “angry” militants in its ranks, the PKK increased the number of its attacks dramatically. The Turkish security apparatus started to seek new ways to handle this “new phenomenon” and (not surprisingly, of course) came up with the idea of using more violence. They created the concept of “fighting terrorists with their own methods.” Kurdish villages were set on fire; 3,000 villages were destroyed. The monster created by the Turkish deep state, JİTEM (an illegal gendarmerie unit), claimed more than 17,000 lives. People were abducted in broad daylight, and their dead bodies later thrown onto streets, under bridges and into wells. No person ever turned up alive after being taken by JITEM. The terror they created, like the terror in the Diyarbakır prison, sent more and more militants to the PKK.

Stuck between a rock and hard place

This is one side of the coin. On the other side, there is the PKK. It was first established as a Marxist-Leninist organization and turned into an extremely nationalist, violent structure. Many times, poor Kurdish villagers were persecuted simultaneously by security forces and the PKK, both of which accused villagers of aiding and abetting “the other” one. The PKK killed many Kurds. The PKK tortured and killed its own militants. The PKK used terrorist attacks, including suicide bombings, exploding bombs in the most crowded streets, and so on. The PKK was ruled by an iron fist. To be honest, for many years I thought the worst thing that could ever happen to the Kurds would be to live under the authority of the PKK, which has the potential of becoming one of the worst dictatorships the world has ever seen.

Today we are at a point where Turkish state officers mention the “Kurdish question” openly, and both the PKK and the Turkish state are about to explain their “road maps” for a solution to the problem. In the past, there were occasions when we all felt so close to the solution. Each time, the “Turkish deep state” and the “deep PKK” found a way to sabotage the whole process. Today, because of the Ergenekon case, we are in a more advantageous situation. At least one “party” has fewer options to sabotage the “process.” But what is this process? Does it include an open confrontation with our past? Does it include both Turks and Kurds questioning taboos? Will it lead us to confront older and deeper wounds in our past, like the Armenian tragedy, which was created by Turks and Kurds together?

My observation is that no one in Turkey is ready for this kind of confrontation. Instead, everyone waits for “the other” to accept their responsibility without sacrificing anything. I strongly believe that if we do not confront this ugly past, if we do not open our hearts to the human suffering, no “solution” will be long lasting. If Kurds do not open their hearts to PKK members who were tortured and killed by the PKK or the Turkish victims of terror created by this organization, likewise if Turks fail to understand the pain and suffering of Kurdish villagers who were wrested from their very roots, we cannot solve anything. This is the first level. At the second level, we need a deeper understanding. Both Turks and Kurds need to confront the Armenian tragedy, which they created together. If Kurds start to understand this tragedy, they will get rid of the illusion that they are the only people who ever suffered in Anatolia. If they understand the Armenian tragedy, and how Kurds were used by the deep state then, they would be much more humble, much less nationalist. We need to question many things. Every answer will lead to other questions. This is a process full of pain. Is anyone ready for that much deep questioning? I don't think so. Unless we engage this kind of questioning, we will inevitably end up with shallow “solutions” which will not be long lasting. If we had understood the Armenian tragedy, we would not have become mired in the Kurdish question. Unless we question our past, some people will try to restore the “deep state” once again, some people will try to re-establish the PKK sometime in the future. Everything depends on severing the moral bases of these terrible structures, and this depends on an open confrontation with everything in the past. Can we start?

Istanbul Diplomacy*, Kerim Balci @todayszaman.com

A city is a type of human settlement that has a soul of its own. Urban settlements, on the other hand, do not. This observation is in fact a subjective one and may be challenged. In my personal universe, İstanbul and Paris are two large cities, and London and New York are urban settlements.

One may love London because of the Thames or because of Soho or because of London Bridge, shopping centers and Hyde Park. There are countless reasons to love London. As former London Mayor Ken Livingstone formulated it: London is the world in one city. But İstanbul is loved because it is İstanbul. Just as a husband feels helpless in the face of his wife asking, “Honey, why do you love me?” the lovers of İstanbul have no explanation for why they love İstanbul other than the fact that “being loved” is intrinsic to “being İstanbul.” Love and identification is a part of the definition of this city.

For some time, I have been observing the love and affection people feel toward İstanbul in almost all the cities of countries founded on the former lands of the Ottoman state. The love of İstanbul is like the grin of the Cheshire Cat in “Alice in Wonderland.” All of the Ottoman past may have disappeared in those post-Ottoman cities, but the love of İstanbul is still there.

My most recent observation of this pure love was from Arbil, the capital city of the Kurdish regional administration in northern Iraq. A Turkmen citizen of Iraq told me how badly he wanted his son to see İstanbul “with the eyes of this world” -- a Turkish saying referring to a desire to see a place or a person before one dies. Just as Muslims all over the world pray to see Mecca and Medina in their lives and as Jews pray for the reconstruction of Jerusalem in their own days, many people around the world feel that urge to see İstanbul.

Only recently, I heard an Uighur from Turkestan refer to İstanbul as the center of their world perceptions. “We look toward İstanbul, and we take our inspirations from İstanbul,” he told a national TV station here in Turkey. The love of İstanbul was packed by the Greeks and Jews that were made to flee this country in the first half of the 20th century. The love of İstanbul was inherited by the second and third generations of Armenians that were exiled from Anatolia in the beginning of that century. I met people that hated Turks for ideological reasons while keeping that love for the city in their hearts.

One may claim that this love is irrational. Which love, then, is rational?

Be it irrational or not, the love for İstanbul is a reality, and it has its external expressions.

This love gives İstanbul a unique power for city diplomacy. City diplomacy can prevail when state-to-state diplomacy fails. Diplomacy between Turkey and Armenia has a lot of prejudices, historical stumbling blocks and misrepresentations to overcome. An alternative can be İstanbul-Yerevan diplomacy. “Turkey speaking to Kurdistan” is a prospect that can annoy many nationalists. İstanbul may speak to Arbil without any ideological, political or nationalistic reservations.

The same is true for identification. Many people who are legally Turkish citizens feel more affection toward a particular city or region in Turkey than they feel toward the country as a whole. I have seen ideologically mobilized Kurds in Europe. They were all Turkish citizens, but they preferred to call themselves Kurds. When it came to speaking about İstanbul, I observed them speaking about the city as one of their cities.

İstanbul can be a social bond between the different segments of Turkish society. It can be a kind of “social contract” embodied in the image of a city.

*A special thanks to Mesut Çevikalp, who opened my eyes to the prospects of the love of Istanbul turning it into a social-diplomatic capital.

28 July 2009

Standing Up To Barack And Company: Armenia, 3m Realpolitik And The Integrity Thing, Raffi K. * Hovannisian , ArmeniaNow

* Armenia's First Minister Of Foreign Affairs

It is often easier to fight for one's principles than to live up to them. In another time but at the same place, presidential contender Adlai Stevenson was setting the scene generations later for President Obama and his administration.

As unfair as it is to be held up as everyone's lighthouse of liberty and justice, Barack Obama was elected president on his self-projection as that very beacon. He and his world-power colleagues, for both principle and posterity, must not allow themselves the comfort, however transient, to play feel-good god in mockery of historical tragedy and in defiance of contemporary imperatives to right the wrongs of the past.

Earlier this month, G8 leaders Obama, Sarkozy, and Medvedev issued a joint declaration softly pre-imposing a superpower solution on Armenia and the freedom-loving people of Artsakh, otherwise known as Mountainous Karabagh. Years before recognition of Kosovo and Abkhazia became current fashion and counter-fashion, Karabagh was the first autonomous territory of the old USSR to challenge Stalin's divide-and-conquer legacy and to raise the standard of decolonization and liberation from its Soviet Azerbaijani yoke by means of a constitutional referendum on independence in December 1991.

Azerbaijan responded to this legitimate quest for self-determination with a failed war of aggression, resulting as it did in tens of thousands of casualties, more than a million refugees, countless lost birthrights, collaterally damaged cultural heritage, and a new strategic balance on both sides of the bitter divide, and so sued for ceasefire in May 1994.

Barack and company now wish for the Armenians, having suffered both an unrequited genocide and the greatest ever of national dispossessions at the hands of Ottoman Turkey nearly a century ago, to cede even more of their ancestral patrimony and their newly-achieved sovereignty by calling on them to withdraw unilaterally from «occupied» areas belonging to the Republic of Mountainous Karabagh in exchange for some foggy-bottomed diplomatic formulation about a future plebiscite.

Armenia says no, thank you.

If President Barack Obama and his distinguished new-age colleagues want to demonstrate that the conscience of humanity has survived the second millennium, that equity can still obtain in international affairs, and that an even and comprehensive application of the law, not self-serving parochial politics, rules this century, then they might wake up to a new mirror and proclaim the following.

- Should Mountainous Karabagh or any of its constituent parts be considered by anybody as occupied, then clearly the historical Armenian heartlands of Shahumian, Getashen, Gardmank, and Nakhichevan must immediately be acknowledged to be under Azerbaijani occupation. Worse yet, official Baku is demolishing, with malice aforethought, the last vestiges of Armenian Christian heritage in its jurisdiction, the most recent documented crime of dastardly proportions having taken place in December 2005 upon the no-longer-existent medieval chapels, cross-stones, and divine offerings at Jugha, Nakhichevan. Had the perpetrator been the Taliban - or the victim a sacred Semitic cemetery - America, Europe, Russia, and all of world civilization would have been rightfully outraged and demanded remedial action forthwith.

- If the rule of law is not a hoax or a decoy or an instrument of whim and duress, then the Mighty Three must together - and simultaneously - recognize Kosovo, Abkhazia, and Mountainous Karabagh as independent states fitting the definitional requirements of the Montevideo Convention. All must be recognized by all, or else none by none. The sui generis argument is distinction without difference.

- The government of republican Turkey - the successor regime bearing the rights and obligations of its genocidal predecessor - can no longer play dog-and-tail tag with the United States, the European Union, and the Russian Federation. Ankara's normally astute diplomacy has forgone the 18-year opportunity since Armenia's declaration of sovereignty to establish official relations with it without the positing by either side of any political preconditions. It has, most unfortunately, done so from the very beginning first by presenting preconditions of its own (including those turning on Karabagh and «occupied» territories), then holding Armenia in an unlawful blockade tantamount to an act of war, and finally speaking the language of blackmail and double-down intrigue with Washington, Brussels, and Moscow.

- Of course, the trinity of power all have talked the walk pursuant to their own petty interests of the day. President Obama's double-speak on genocide and its shameful denial, at Ankara in April followed by Buchenwald in June, is a classic in point. But if Obama and friends are serious about the new global order, then they might find the fortitude to remind Turkey, as key partner and good neighbor, that it stands in occupation of the ancient Armenian homeland and owes a debt of atonement and redemption to the Armenian nation. And no crowning Bolshevik-Kemalist compact from 1921, a full generation before Molotov-Ribbentrop, can serve to rationalize the great genocide, nor purport to regulate the relations and frontiers between the modern Republics of Turkey and Armenia. That is their sovereign duty mutually to resolve, but if anyone in Washington or elsewhere requires guidance on crimes against humanity, ways and means of restitution, and definitions of occupation, «the memory hole» of expedient forgetting can be duly overcome in the US National Archives, its records on the Armenian genocide, and most poignantly the provisions of President Woodrow Wilson's arbitral award, issued under his seal in November 1920 and legally controlling to this day, to Armenia and its people.

Now, who was taking that pledge to liberty and justice for all? It was us, and Obama: «We must be ever-vigilant about the spread of evil in our own time, that we must reject the false comfort that others' suffering is not our problem, and commit ourselves to resisting those who would subjugate others to serve their own interests.»

National Assembly Deputy Raffi K. Hovannisian is founder of Heritage political party and was independent Armenia's first Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Conscious Existence? What Does it Mean to be Armenian?, 2009/07/27, Seda Grigoryan

I don’t know. Must I pass all this down to my kids or not ? I don’t know. Should I continue to remain Armenian or just get on with life?

These are two types of “existence” of the scale that don’t fully equate but that counterbalance the other given the dictates of reality – to live or remain Armenian.

The young French-Armenian woman came clean on behalf of all diaspora youth who wage another battle in the overall battle of daily life – to remain Armenian. Is the preservation of Armenian identity given such prominence and thought; is it that mandatory? Isn’t it hard enough just to live without trying to maintain ones national identity in a society where western values hold sway? Such questions are faced by many diaspora Armenian youth who still recognize their Armenian roots and who say that they are Armenian, in addition to being French, Belgian and American.

20 year-old Rouben – “I feel different from the French”

«When you’re young you don’t give the matter much thought. But when you grow up you feel that you are different from the French. This is especially so when it comes to the family; which is very important. Our families are stricter and relatives are more respected. We visit our grandparents and cousins. Our upbringing is also different. When you grow up in France you feel these differences,” twenty year-old Rouben said. He decided to learn Armenian after visiting Armenia last year.

A student at the Sorbonne’s history department, the fact that he has resided at the “Armenian Student House” in Paris, rubbing shoulders with other Armenian students from various countries, really made him appreciate his Armenian roots. He says that it allowed him to mould his Armenian identity. In addition, he proved to himself and others that it’s possible to learn Armenian rather quickly if the desire exists, since being Armenian is more than just words.

While Rouben is probably not unique, it would be stretching it to say that his level of enthusiasm is commonplace. In the diaspora today, the fourth generation of Genocide survivors is being born. Naturally, the place they are born is where they call home. This is especially the case in the West where they live along side of other nationalities and where their integration into the dominant society is at a level where talk about national identity and roots often become superfluous. Over time and with succeeding generations these concepts are often forgotten.

This danger of assimilation also threatens Armenians. Many are worried that Armenians in the diaspora will soon become a “nation of grandparents”.

This is the reason why many families continue to pass along the Armenian language, history and traditions to their children.

What does it mean to be Armenian? The young people we spoke to singled out four necessary factors to remain Armenian – language, religion, culture and family.

Sadly, for some, being Armenian connotates living in a closed-society with restrictions; barriers that have been or are being placed as a way to ward off the encroaching threats of assimilation.

Does one have to speak the language to be Armenian?

Rouben believes that if you speak Armenian to your children then you are Armenian, because you are always using the language of your heart to converse with your child.

Hagop Talatinian was born and raised in Lebanon, in a family that spoke Armenian. He went to an Armenian school. His only concern today is that his children speak Armenian since he wants to transfer that “treasure” to them.

“My grandfather’s family learned Armenian under difficult conditions. They tell the story of learning Armenian on the desert sands; I feel a certain obligation to my grandfather and mother for trying to preserve this value. We have a debt of respect to pay back. This is why I can’t tell myself that I am not Armenian. I can’t, because I have to look my father in the face. The eyes of my father and mother will tell me – those values that I gave you…When a child is born you don’t say – let’s see what clothes he wants to wear. You clothe the child so that later on the child can decide whether he likes the clothes or not. It’s the same with religion and the language,” says Hagop Talatinian.

Mkrtich Basmajian, who directs a theater group in Paris that stages plays in Armenian, has realized that one can remain Armenian in the diaspora only through the parallel efforts of the school and church. However, especially in the west, the growth of Armenian language usage is dubious. If there are still those who are interested in learning the language, their numbers have drastically decreased when compared with the previous generation.

Recently, “Haratch” the last remaining Armenian language newspaper in France, if not all of Europe, closed down. It first was published in 1925. Over the years the paper was in great demand in the French-Armenian community, not only as a source of information but because it was published in Armenian. Many say that their parents and grandparents looked forward to each new issue because it served as a link to the “lost” homeland. Why did “Haratch” shut down when the Armenian community in France is bigger than ever?

Today, in the diaspora, Armenian plays a more symbolic role than as a means of communication or dialog. Despite the fact that Armenian schools continue to function, Armenian isn’t spoken in many families as the primary language.

Labels such as « Our language is holy, a treasure” merely serve to consign the language to further disuse. “In my opinion, it is very dangerous to state that our ABC’s are holy letters because the more they are sanctified they more the letters become encases in stone, like “khatchkars”. We can’t modernize those values and pass them on,” said twenty-four year-old Tigran Yekavyan.

Tragically, the principle of « preservation » is more in vogue in the diaspora today since what is « new » is perceived to hold the threat of integration into western culture.

« The preservation of the Armenian identity ‘hayapahpanoum’ and the culture turn into something akin to a jar of preserves. In other words, I have to place everything, language, customs, and symbolic items into that jar and shut it tight. For me, the development of the Armenian is important. Rather than encouraging the new generation and new talents, we’ve chosen classicism; the preservation of our past inheritance that has survived. For another fifty years we’ll be reciting the same poetry; Siamanto for example. People will understand nothing but will continue the traditions,” continued Tigran Yekavyan, a graduate of the Paris School of Political Science.

While true that Armenian organizations continue working to keep the Armenian culture and history alive, in the opinion of young people, these efforts revolve around one issue – the Genocide.

The Genocide isn’t a basis for national identity

Noyem Hapoujian says, « I’ve been cut off from the Armenian community for many years. Now, I’ve returned to the fold. I’ve never understood why we experience such pain. Is it due to the Genocide? These themes of pain and being victims are stressed to the point that we can’t culturally interact with other nations. I attend cultural events and festivals of other nationalities but rarely do I meet other Armenians there. I would like to see Armenians open up culturally. Why are we so closed as a community? There is the constant fear that we will lose the culture. It’s as if it’s a treasure that can’t be touched. We must learn to give since it’s important to create dialog with other nations. Being Armenian isn’t just about suffering; it’s a very rich cultural tradition. As children they teach about the Genocide and religion. But religion, for me, isn’t culture. It is necessary to build a national identity on the basis of culture and not the Genocide.”

Most of the people I talked to said that the bulk of events now being organized in the diaspora revolve around the Genocide. It’s an issue that unites all Armenians in the diaspora and there is a broad consensus of opinion on the subject. As Mkrtich Basmajian noted, “There’s a sensory nerve that must be set off to feel Armenian and it relates to 1915.”

The black chapter of Armenian history is so stressed in the diaspora today that oftentimes the history and culture of the Armenian people up till 1915 is forgotten.

Belgian-Armenian Peter Boghosian says, « Our history isn’t just the Genocide. The best way struggle against that tragic episode is to present our history to the world. We should not forget that Armenians contributed a great deal in the formation of the Ottoman Empire. Some of the largest palaces were built by Armenians.”

Many in diaspora do not view RoA as their homeland

A young French-Armenian woman confessed that she wasn’t even aware of the existence of the Republic of Armenia (RoA). In the minds of many, the name “Armenia” conjures up the “erkir” (lost homeland) of the past. These people don’t see their future as linked to present-day Armenia.

Peter said, « If they give back the lands in Cilicia tomorrow, I would go and live there. But the RoA isn’t the land of my ancestors; it’s a symbol. I really loved the RoA when I visited but it isn’t our Armenia. Our roots come from an Armenia where we lived side by side with Greeks, Turks, Arabs and Jews.”

In the diaspora, Genocide recognition is the unifying factor

All Armenian organizations active in the diaspora today target their primary activities on the international recognition of the Genocide. In other words, the denial by Turkey of the Genocide serves to unite the Armenian diaspora. What would happen if Turkey one day recognizes the Genocide?

Shant Habibian, a member of the « Nor Seround » (AYF in France), says that, »The number one aim for our meetings is to tell the youth about Armenian massacres and secondly, for them to grow up Armenian. We have an Armenian paper. Perhaps it is because Turkey denies the Genocide that we have considered ourselves Armenian for all these years. It’s been a source of strength.”

Raffi Der-Hagopian, President of the AGBU’s Paris youth branch says that a host of issues are discussed at youth events but it is April 24th that unites everyone.

“That problem, of constantly talking about the Genocide really kills me. On the day that Turkey recognized the Genocide Armenians will be in a panic since we’ve concentrated on that black page of our history for so long. We’ll be at a loss to what to do next, Raffi says.

This question truly concerns many, but it is raised by only a few.

Being Armenian means struggling every day

“It’s very difficult to explain to a French person that I’m Armenian. They tell me – ‘but you were born here; your parents are here.’ However, Armenian blood flows through my veins. I feel very Armenian and very French at the same time. We have two worlds – the Armenian one, my family, and the French one, the surrounding society. You struggle daily to unite the two somehow, says Raffi Der-Hagopian.

Luckily, there are still many families in the diaspora they are trying to preserve their national identity, passing on, sometimes forcing “Armenian values” on their children through education. These values are perceived differently in different families – language, religion and culture are typical traits of the Armenian family.

“Up until the age of fifteen I had a strong sense of being Armenian and was quite proud of it. I remember writing a report when I graduated entitled, ‘If I hadn’t been born Armenian, I would have liked to’. But at the age of 17 or 18 I started to think differently. Naturally you begin to ponder things like – who am I, what am I, where do I come from, and do I like what I am? I realized that my parent’s education has influenced the way I see many things. But there are many things about it that I didn’t like and still don’t but tolerate because of my parents. I do not deny being Armenian nor am I ashamed of it. I understand them and that they went through hard times as well. But when they try to pass along all this to young kids it’s like brainwashing. In the end, when you turn 17 you start to think about these things and understand that it’s an “overdose”, said Greek-Armenian Ani.

Aside from this inculcation, many families force their kids to marry only Armenians. Perhaps, it’s out of a fear that assimilation will gradually result in the disappearance of the Armenian identity. Or perhaps, it’s merely out of concern for one’s children and the wish that they have a strong family; something that they believe can only be formed by marrying an Armenian.

Marrying “odars” still a taboo?

“Even till today, my father can’t cope with the fact that I might marry a non-Armenian. It’s out of the question. It’s understandable in a way since we are a small nation and don’t have the “luxury” of marrying non-Armenians and thus disappearing,” said Tigran Yekavyan.

26 year-old Narek, who spent his youth in one of the African countries, where there were only a handful of Armenian families, recounted that he rejected his being Armenian while young. He explains that this was the case because when others don’t understand who you are, integration becomes difficult in that society. Then too, accepting his Armenian roots came to symbolize the authority of his parents.

“I agreed to everything that my parents forced on me; the education of a well-mannered boy that doesn’t get into mischief. The first time I started to date an Arab girl and told my parents about it, they saw it as a dangerous thing. My mother fell ill. There was pressure every day in my family. I wanted to stay with that girl, but it was taboo according to Armenian tradition. There were many other girls that I liked but I put an end to things. If I let the relationships get serious it would have only created more pain. Then too, I really wish to please my folks. Armenians are altruistic; they go out of their way to please others. During moments of weakness, I often told myself that I wished to have been an Arab,” says Narek.

Today, Narek positively regards the education given by his parents. It’s hard to say how sincere he was when he assured us that in the depths of his soul perhaps he also wanted it to be thus.

“When you grow a bit tired and move away a bit, you feel that need. Even when you grow tired of all the events and such, you can’t really distance yourself that much. Whether or not you distance yourself, you feel that longing. It’s like a rubber band; the more you stretch it, the stronger it springs back,” noted Shant Habibian.

Monte Melkonian as symbol of diaspora contradiction

American-Armenian Raffi Barsoumian spent his youth in the company of Armenians and spoke Armenian in the home with the family. Only after going away to college did he think about the necessity of preserving his national identity.

“For many years I lived far-away and began to think, what will I do now? I’ll get married, work at different things and maybe lose direction. You think to yourself that life is life and that all men are just like others; why not. But the other day my friend sent me a clip of Monte Melkonian on “you-tube”. You know he was born and raised in California, an American, who became a soldier. When you watch his story you realize that there are other people out there, other nations. You can go become an American or a Frenchman, but it’s a pity. There are people who gave their lives, to protect and preserve that which you have in your blood,” says Raffi.

P.S. The idea for this article resulted from a discussion that took place after the staging of Mkrtich Basmajian’s “Broken Dreams”. The essential question that was raised during the discussion by the youth that evening was what should be done in the future. Was it really necessary to pass on this “heavy burden” to future generations as well? For this burden includes one’s Armenian roots, the history, especially the Genocide, and on the other hand, Armenian pride. Naturally, having been born on foreign soil, these young people are not only Armenian. However, it is also clear that there is something that pulls them close to their Armenian roots. Many we spoke too quietly confessed that they had often thought about how easy life would be if they weren’t Armenian but that deep down inside the Armenian within always pulled them back, no matter how hard they tried to escape.

Seda Grigoryan is a reporter for “Hetq”. She currently attends the The Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO) is located in Paris and is defending her thesis in linguistics.

Why Don't Jews Condemn Anti-Semitism In Turkey?, Harut Sassounian , Publisher, The California Courier

Rifat Bali, a Jewish scholar and a native of Istanbul, has been investigating anti-Semitism in Turkey for many years. He has authored several books and articles on the history of Turkish Jews. His most recent book, "The Jews of Turkey and the Armenian Genocide," is a monumental work that documents how the Turkish government pressured not only Turkish Jews, but also the Israeli government and American-Jewish organizations, to lobby against congressional resolutions on the Armenian Genocide.

Turkey's blackmail of Jews in and out of Turkey is not news to our readers. Neither is the fact that there has been widespread anti-Semitism in Turkey for decades, if not centuries. In a lengthy article published in July by the Institute for Global Jewish Affairs in Jerusalem, Mr. Bali meticulously documents the fact that such racist attitudes are held by practically the entire spectrum of Turkish society.

In his article, "Present-day Anti-Semitism in Turkey," Mr. Bali summarizes his analysis in four key points:

· "Turkish intellectuals have always taken a pro-Palestinian and anti-Israeli stance. Islamists associate the 'Palestine question' with alleged Jewish involvement in the rise of Turkish secularism. Leftists see Israel as an imperialist state and an extension of American hegemony in the Middle East. Comparable themes are found among nationalist intellectuals.

· "Turkish reactions to Israel's 2006 war in Lebanon and 2009 war in Gaza often spilled over into anti-Semitism. Newspaper columnists, some of them academics, belonging to the various ideological streams helped fan popular sentiment against Israel and Jews. Israel was said to be exploiting Holocaust guilt and the services of the 'American Jewish lobby' to further its own nefarious aims.

· "Turkish approaches to the 'Palestine question' rarely venture outside the clichés of Turkish popular culture. Turkish publishing houses providing translated works on the issue are careful not to run afoul of popular sentiment. The net result is that both Turkish columnists and their readers utilize only limited sources on the conflict that are preponderantly anti-Israeli and anti-Semitic.

· "Any attempt by the Turkish Jewish leadership to confront Turkish society on combating anti-Semitism is likely to backfire and even further exacerbate the problem. Given this reality, the only options left for Turkey's Jewish community are to either continue living in Turkey amid widespread anti-Semitism or to emigrate."

Mr. Bali documents his assertions by quoting from dozens of anti-Semitic statements published in various Turkish newspapers in recent years. Here are some examples:

-- Toktam?? Ate?, professor of political science at Istanbul and Istanbul Bilgi universities, newspaper columnist, and a prominent intellectual who frequently appears on TV, described Jews as "the first and most racist people in history." (Bugün, July 20, 2006).

-- Ayhan Demir, a commentator for the Islamist Millî Gazete , wrote: "The first thing to be done to achieve the security of Istanbul and Jerusalem is to get rid of, in as short a time as possible, this 'shanty town' that has begun to harm humanity on the entire face of the earth, and which is as offensive to the heart as to the eye. To send the occupiers to the garbage heap of history, together with their bloody charlatanism would be one of the most noble acts that could be realized in the name of humanity. A world without Israel would be, without a doubt, a much more peaceful and secure world."

(Milli® Gazete, December 30, 2008).

-- Nuh Gönülta?, a well-known columnist, said Hitler was justified in his treatment of the Jews, since "the state of Israel is an even greater tyrant than Hitler." (Bugün, August 1, 2006).

-- The Islamist sociologist Ali Bulaç, a well-known columnist for Zaman, described Gaza as "a concentration camp that in reality surpasses the Nazi camps." (Zaman, December 29, 2008).

It is simply astonishing that Israeli officials and Jewish leaders worldwide hardly ever react, at least not publicly, to such widespread and vicious anti-Semitic outbursts in Turkey. Why is Rifat Bali resigned to the fact that "the only options left for Turkey's Jewish community are to either continue living in Turkey amid widespread anti-Semitism or to emigrate?" This is a fundamental question that Jews themselves should answer!

By keeping quiet, Jewish leaders are simply encouraging Turkish commentators to continue making racist and insulting remarks. If Israel's President Shimon Peres and ADL's National Director Abraham Foxman were not so busy denying the Armenian Genocide, they would perhaps spend more of their time fighting anti-Semitism!

'The Next 100 Years' May Not Bode Well For Armenia, Andy Turpin, Asbarez, Jul 27th, 2009

Corporate Intelligence Guru George Friedman's Latest Book Predicts Turkish Superpower

WATERTOWN, Mass. (A.W.)--To personify the tone of George Friedman's newest book of speculative geopolitics, The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century (Doubleday, 2009), I shall quote F.D.R. when he allegedly said of Nicaraguan despot and U.S. proxy Anastasio Somoza GarcÃ: "Somoza may be a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch."

Likewise, I will say of Friedman that while I'd probably disagree with his personal social views if seated beside him at a dinner party, there was little in his book's research or analysis that I--nor, I'm assuming, any charter member of the ANCA--would disagree with that staunchly.

Friedman is the chief executive of STRATFOR, the leading private global intelligence firm he founded in 1996. The son of Hungarian Holocaust survivors and raised in New York City, he spent almost 20 years in academia prior to joining the private sector, teaching political science at Dickinson College. During that time, he regularly briefed senior commanders in the armed services on security and national defense matters, as well as those in the Office of Net Assessments, the SHAPE Technical Center, the U.S. Army War College, the National Defense University and the RAND Corporation.

For all intents and purposes, I have honed my review to focus on Friedman's predictions for Armenia, Turkey, and the Caucasus, although his general outline for a realistic 21st-century timeline is as ruthless and American-interest driven--never to be confused with the goals of true American values--as any State Department report I've ever perused.

Keenly, of all U.S. foreign policy decisions, Friedman writes with veritas that the U.S. "has no key interest in winning a war outright. As with Vietnam or Korea, the purpose of these conflicts is simply to block a power or destabilize the region, not to impose order. In due course, even outright American defeat is acceptable. However, the principle of using minimum force, when absolutely necessary, to maintain the Eurasian balance of power is--and will remain--the driving force of U.S. foreign policy throughout the 21st century. There will be numerous Kosovos and Iraqs in unanticipated places at unexpected times... But since the primary goal will more likely be simply to block or destabilize Serbia or al Qaeda, the interventions will be quite rational. They will never appear to really yield anything nearing a 'solution,' and will always be done with insufficient force to be decisive."

In short, Friedman predicts that following the August 2008 war in Georgia, conflicts in the Cauc asus will remain relatively stable until roughly 2020, at which point "Americans will see Russian domination of Georgia as undermining their position in the region. The Turks will see this as energizing the Armenians and returning the Russian army in force to their borders. The Russians will become more convinced of the need to act because of this resistance. A duel in the Caucasus will result... But it will be Europe [namely the Polish border and the Baltic states], not the Caucasus that will matter."

He continues of this proposed conflict: "The Turks will make an unavoidable strategic decision around 2020. Relying on a chaotic buffer zone to protect themselves from the Russians is a bet they will not make again.

This time they will move north into the Caucasus, as deeply as they need to in order to guarantee their national security in that direction... The immediate periphery of Turkey is going to be unstable, to say the least. The United States will encourage Turkey to press north in the Caucasus and will want Turkish influence in Muslim areas of the Balkans."

In Friedman's view, the opening of the border between Turkey and Armenia can be postponed but is inevitable. And when it finally occurs, the Tashnag nightmare scenario--of the Armenian market being flooded with Turkish goods, and Turkey taking over all industrial sectors, leading to Armenian economic serfdom and client state status--will also be unavoidable.

The difference is that like a therapist objectively and impassively listening to someone's problems, Friedman comments but doesn't care about Armenia's interests. He simply notes that such an outcome will be deemed by the U.S. to be in America's interest, before the country makes adequate progress in transitioning to more sustainable "green" energy policies.

By 2040, Friedman writes, an Armenian, Greek, and pro-West anti-Turkish movement will begin to coalesce as the U.S. and Britain no longer regard Turkey as a friendly ally but as the rival superpower against the U.S. alongside a rejuvenated militant Japan.

"Turkey will move decisively northward into the Caucasus as Russia crumbles. Part of this move will consist of military intervention, and part will occur in the way of political alliances," he writes.

"Turkey's influence will be economic--the rest of the region will need to align itself with the new economic power. And by the mid-2040's, the Turks will indeed be a major regional power. There will be conflicts.

From guerilla resistance to local conventional war, all around the Turkish pivot. Turkey will wind up pushing against U.S. allies in southeastern Europe and will make Italy feel extremely insecure with its growing power."

In Friedman's view, such a build-up will eventually lead t o a limited-World War conflict between the U.S. and Poland against Turkey and Japan for divided world hegemony around 2050, with any actual ground combat occurring primarily in the vicinity of the Balkans and the Polish border areas surrounding U.S. and Turkish military targets.

Naturally it remains to be seen what will occur on the world stage, but like Groopman's How Doctors Think (Mariner, 2008), Friedman's Next 100 Years is as best an educated guess as anyone in the geopolitical analysis field can give, pending all variables--and that's something.

Though to my chagrin, no travel agency will take reservations to Armenia for my personal Nuevo-Lincoln Brigade 38th and 68th Birthday Party Artsakh Liberation Extravaganza this far in advance. I checked.

History, Used And Abused, Chris Patten*

LONDON -- In her brilliant book, “The Uses and Abuses of History” the historian Margaret MacMillan tells a story about two Americans discussing the atrocities of Sept. 11, 2001.

One draws an analogy with Pearl Harbor, Japan's attack on the US in 1941. His friend has no idea as to what this means. “You know,” the first man replies, “it was when the Vietnamese bombed the American fleet and started the Vietnam War.”

Historical memory is not always quite as bad as this. But international politics and diplomacy are riddled with examples of bad and ill-considered precedents being used to justify foreign policy decisions, invariably leading to catastrophe.

Munich -- the 1938 meeting between Adolf Hitler, Édouard Daladier, Neville Chamberlain and Benito Mussolini -- is a frequent witness summoned to court by politicians trying to argue the case for foreign adventures. Britain's disastrous 1956 invasion of Egypt was talked about as though Gamal Nasser was a throwback to the fascist dictators of the 1930s. If he were to be appeased as they had been, the results would be catastrophic in the Middle East.