The 2010 narrative report for Armenia is finalized. Please find it on this page.

The 2010 narrative report for Armenia is finalized. Please find it on this page. *Countries are ranked on a scale of 1-7, with 1 representing the highest level of freedom and 7 representing the lowest level of freedom.. . .

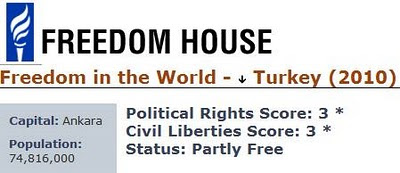

Turkey received a downward trend arrow due to the Constitutional Court’s decision to ban the pro-Kurdish Democratic Society Party.

Overview

The government in 2009 made promising overtures to Kurdish separatists in the southeast, raising hopes for an end to fighting and an expansion of Kurdish rights. However, violent protests erupted late in the year after the Constitutional Court banned the major pro-Kurdish party in December. Also in 2009, the government continued its expansive investigation into an alleged right-wing conspiracy to trigger a military coup.

Turkey emerged as a republic following the breakup of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. Its founder and the author of its guiding principles was Mustafa Kemal, dubbed Ataturk (Father of the Turks), who declared that Turkey would be a secular state. He sought to modernize the country through measures such as the pursuit of Western learning, the use of the Roman alphabet instead of Arabic script for writing Turkish, and the abolitionof the Muslim caliphate.

Following Ataturk’s death in 1938, Turkey remained neutral for most of World War II, joining the Allies only in February 1945. In 1952, the republic joined NATO to secure protection from the Soviet Union. However, Turkey’s domestic politics have been unstable, and the military—which sees itself as a bulwark against both Islamism and Kurdish separatism—has forced out civilian governments on four occasions since 1960.

The role of Islam in public life has been one of the key questions of Turkish politics since the 1990s. In 1995, the Islamist party Welfare won parliamentary elections and joined the ruling coalition the following year. However, the military forced the coalition government to resign in 1997, and Welfare withdrew from power.

The governments that followed failed to stabilize the economy, leading to growing discontent among voters. As a result, the Justice and Development (AK) Party won a sweeping majority in the 2002 elections. The previously unknown party had roots in Welfare, but it sought to distance itself from Islamism. Abdullah Gul initially served as prime minister because AK’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, had been banned from politics due to a conviction for crimes against secularism after he read a poem that seemed to incite religious intolerance. Once in power, the AK majority changed the constitution, allowing Erdogan to replace Gul in March 2003.

Erdogan oversaw a series of reforms linked to Turkey’s bid to join the European Union (EU). Accession talks officially began in October 2005, but difficulties soon arose. Cyprus, an EU member since 2004, objected to Turkey’s support for the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is not recognized internationally. EU public opinion and some EU leaders expressed opposition to Turkish membership for a variety of other reasons. This caused the reform process to stall, and Turkish popular support for membership declined even as Turkish nationalist sentiment increased.

Ahmet Necdet Sezer’s nonrenewable term as president ended in May 2007. Sezer had been considered a check on any extreme measures the AK-dominated parliament might introduce, and the prime minister’s nomination of a new president was closely watched. Despite objections from the military and the secularist Republican People’s Party (CHP), Erdogan chose Gul. In a posting on its website, the military tacitly threatened to intervene if Gul’s nomination was approved, and secularists mounted huge street demonstrations to protest the Islamist threat they perceived in his candidacy. An opposition boycott of the April presidential vote in the parliament prevented a quorum, leading the traditionally secularist Constitutional Court to annul the poll. With his nominee thwarted, Erdogan called early parliamentary elections for July.

AK won a clear victory in the elections, increasing its share of the vote to nearly 50 percent. However, because more parties passed the 10 percent threshold for entering the legislature than in 2002, AK’s share of seats decreased slightly to 340. The CHP together with its junior partner, the Democratic Left Party, won 112 seats. The Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) entered the assembly for the first time, with 70 seats. A group of 20 candidates from the pro-Kurdish Democratic Society Party (DTP) also gained seats for the first time by running as independents, since they did not have the national support required to enter as a party. Other independents won the remaining 8 seats. The MHP decided not to boycott the subsequent presidential vote, and Gul was elected president in August.

In an October 2007 referendum, voters approved constitutional amendments that, among other changes, reduced the presidential term to five years with a possibility for reelection, provided for future presidents to be elected by popular vote, and cut the parliamentary term to four years. The new parliament began drafting a new constitution, but progress later stalled.

In 2008, long-standing tensions between the AK government and entrenched, secularist officials erupted into an ongoing investigation focused on an alleged secretive ultranationalist group called Ergenekon. A total of 194 people were charged in three indictments in 2008 and 2009, including military officers, academics, journalists, and union leaders. A trial against 86 people began in October 2008, and a second trial against 56 people began in July 2009. Ergenekon was blamed for the 2006 bombing of a secularist newspaper and a court shooting that killed a judge the same year; its alleged goal was to raise the specter of Islamist violence so as to provoke a political intervention by the military. Critics argued that the government was using the far-reaching case to punish its opponents.

The government in 2009 made positive overtures to the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), a separatist group that has fought a decades-long guerrilla war against government forces in the southeast. The moves raised hopes of a permanent ceasefire; an earlier halt in fighting had lasted from 1999 to 2004. However, the state’s relations with the Kurdish minority suffered a serious blow in December, when the Constitutional Court banned the DTP on the grounds that it had become “a focal point for terrorism.”

Political Rights and Civil Liberties

Turkey is an electoral democracy. The 1982 constitution provides for a 550-seat unicameral parliament, the Grand National Assembly. Reforms approved in a 2007 referendum reduced members’ terms from five to four years. The changes also envision direct presidential elections for a once-renewable, five-year term, replacing the existing system of presidential election by the parliament for a single seven-year term. The president appoints the prime minister from among the members of parliament. The prime minister is head of government, while the president has powers including a legislative veto and the authority to appoint judges and prosecutors. The July 2007 elections were widely judged to have been free and fair, with reports of more open debate on traditionally sensitive issues.

A party must win at least 10 percent of the nationwide vote to secure representation in the parliament. The opposition landscape changed in 2007, with the entrance of the MHP and representatives of the DTP into the legislature. By contrast, only the two largest parties—the ruling AK and the opposition CHP—won seats in the 2002 elections.

A party can be shut down if its program is not in agreement with the constitution, and this criterion is interpreted broadly. In December 2009, the Constitutional Court closed the DTP and banned many of its members from politics, including the removal of two parliamentarians from office. Those remaining in parliament regrouped under the new Peace and Democracy Party. Major protests followed that were often violent and even deadly.

Reforms have increased civilian oversight of the military, but restrictions persist in areas such as civilian supervision of defense expenditures. The military continues to intrude on issues beyond its purview, commenting on key domestic and foreign policy matters. The fact that the military ultimately did not act on its tacit threats to disrupt the 2007 election of Abdullah Gul as president was considered a sign of progress. A 2009 law restricting the use of military courts brought Turkey closer to EU norms, but the measure is being contested by the opposition.

Turkey struggles with corruption in government and in daily life. The AK government has adopted some anticorruption measures, but reports by international organizations continue to raise concerns, and allegations have been lodged against AK and CHP politicians. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been accused of involvement in a scandal over the misuse of funds at a charity called Lighthouse. A German court handling charges related to the scandal has implicated the head of Turkey’s broadcasting authority. Government transparency has improved under a 2004 law on access to information. Turkey was ranked 61 out of 180 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index.

The right to free expression is guaranteed in the constitution, but legal impediments to press freedom remain. A 2006 antiterrorism law reintroduced jail sentences for journalists, and Article 301 of the 2004 revised penal code allows journalists and others to be prosecuted for discussing subjects such as the division of Cyprus and the 1915 mass killings of Armenians by Turks, which many consider to have been genocide. People have been charged under the same article for crimes such as insulting the armed services and denigrating “Turkishness”; very few have been convicted, but the trials are time-consuming and expensive. An April 2008 amendment changed Article 301’s language to prohibit insulting “the Turkish nation,” with a maximum sentence of two instead of three years, but cases continue to be brought under that and other clauses. For example, in 2009 a journalist who wrote an article denouncing what he said was the unlawful imprisonment of his father, also a journalist, was himself sentenced to 14 months in prison. A journalist was also shot near his office in December 2009. In a positive development the previous year, a court overturned a government ban on reporting about Ergenekon. Journalists have been among those implicated in the Ergenekon case.

Nearly all media organizations are owned by giant holding companies with interests in other sectors, contributing to self-censorship. In 2009, the Dogan holding company, which owns many media outlets, was ordered to pay crippling fines for tax evasion in what was widely described as a politicized case stemming from Dogan’s criticism of AK and its members. The internet is subject to the same censorship policies that apply to other media, and a 2007 law allows the state to block access to websites deemed to insult Ataturk or whose content includes criminal activities. This law has been used to block access to the video-sharing website YouTube since 2008, as well as several other websites in 2009.

Kurdish-language publications are now permitted. The last restrictions on television broadcasts in Kurdish, which began in 2006, were lifted in 2009, some months after a 24-hour Kurdish-language channel began broadcasting. However, Kurdish newspapers in particular are often closed down and their websites blocked, and some municipal officials in the southeast have faced criminal proceedings for communicating in Kurdish.

The constitution protects freedom of religion, but the state’s official secularism has led to considerable restrictions on the Muslim majority and others. Observant men are dismissed from the military, and women are barred from wearing headscarves in public universities and government offices. An AK-sponsored constitutional amendment passed in February 2008 would have allowed simple headscarves tied loosely under the chin in universities, but the Constitutional Court struck it down in June of that year. In the interim, many universities had defied the changes and continued to enforce the total ban. Separately in 2008, the parliament passed a new law that eases restrictions on religious foundations.

Three non-Muslim groups—Jews, Orthodox Christians, and Armenian Christians—are officially recognized, and attitudes toward them are generally tolerant, although they are not integrated into the Turkish establishment. Other groups, including non-Sunni Muslims like the Alevis, lack legal status, and Christian minorities have faced hostility; three Protestants were killed in April 2007 at a publishing house that distributed Bibles.

The government does not regularly restrict academic freedom, but self-censorship on sensitive topics is common. An academic who suggested that the early Turkish republic was not as progressive as officially portrayed was sentenced to a 15-month suspended jail term in 2008.

Freedoms of association and assembly are protected in the constitution. Prior restrictions on public demonstrations have been relaxed, but violent clashes with police still occur. The annual clashes between police and May Day protesters were less severe in 2009. A 2004 law on associations has improved the freedom of civil society groups, although 2005 implementing legislation allows the state to restrict groups that might oppose its interests. Members of local human rights groups have received death threats and sometimes face trial. Nevertheless, civil society is active on the Turkish political scene.

Laws to protect labor unions are in place, but union activity remains limited in practice. While some obstacles have been removed in recent years, Turkey still does not comply with international standards on issues such as collective bargaining.

The constitution envisions an independent judiciary. The government in practice can influence judges through appointments, promotions, and financing, though much of the court system is still controlled by strict secularists who oppose the current government. A 2009 scandal revealed official wiretapping of judges, leading to accusations of political interference. The judiciary has been improved in recent years by structural reforms and a 2004 overhaul of the penal code, and a promising reform strategy was approved in 2009. The death penalty was fully abolished in 2004, and State Security Courts, where many human rights abuses occurred, were replaced by so-called Heavy Penal Courts. However, Amnesty International has accused the Heavy Penal Courts of accepting evidence extracted under torture. The court system is also undermined by procedural delays, with some trials lasting so long as to become a financial burden for the defense.

The current government has enacted new laws and training to prevent torture, including a policy involving surprise inspections of police stations announced in 2008. The 2009 government human rights report found that torture and ill-treatment are declining, although the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey in 2008 reported much higher numbers and a slight increase in violence and ill-treatment since 2005. A man arrested for participating in a demonstration died in custody in October 2008, after he was allegedly beaten; 60 police and prison officials were indicted. Prison conditions can be harsh, with overcrowding and practices such as extended isolation in some facilities. In 2009 jailed PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan was moved to a new facility, ending his controversial solitary confinement.

Also in 2009, the government began serious peace negotiations with the PKK to end the Kurdish conflict in the southeast, including the announcement of a major government initiative to improve democracy and minority rights. However, the fate of this initiative is in doubt since the banning of the DTP sparked protests at year’s end. Bombings in other parts of the country by various radical groups are not infrequent, although there were no serious incidents in 2009.

The state claims that all Turkish citizens are treated equally, but because recognized minorities are limited to the three defined by religion, other minorities and Kurds in particular have faced restrictions on language, culture, and freedom of expression. The situation has improved with EU-related reforms, including the introduction of Kurdish-language postgraduate courses in 2009. However, alleged collaboration with the PKK is still used as an excuse to arrest Kurds who challenge the government.

A 2008 Human Rights Watch report found that gay and transgender people in Turkey face “endemic abuses,” including violence, and a local report found widespread discrimination, especially in the workplace. Istanbul’s largest gay and transgender organization, Lambda, won an appeal against its closure in 2009, but a prominent transgender human rights activist was stabbed to death soon thereafter. Advocates for the disabled have criticized lack of implementation of a law designed to reduce discrimination. Also in 2009, an Amnesty International report criticized Turkey’s asylum policy, which does not recognize non-Europeans as refugees, and the European Court of Human Rights ruled that two Iranian refugees had been unlawfully detained while seeking asylum in Turkey.

Property rights are generally respected in Turkey, with the exception of the southeast, where tens of thousands of Kurds were driven from their homes during the 1990s. Increasing numbers have returned under a 2004 program, and some families have received financial compensation, but progress has been slow. Local paramilitary “village guards” have been criticized for obstructing the return of displaced families through intimidation and violence.

The amended constitution grants women full equality before the law, but the World Economic Forum ranked Turkey 129 out of 134 countries surveyed in its 2009 Global Gender Gap Index. Women held just 49 seats in the 550-seat parliament after the 2007 elections, though that was nearly double the previous figure. Domestic abuse and so-called honor crimes continue to occur; a 2007 study from the Turkish Sabanci University found that one in three women in the country was a victim of violence. Suicide among women has been linked to familial pressure, as stricter laws have made honor killings less permissible; the 2004 penal code revisions included increased penalties for crimes against women and the elimination of sentence reductions in cases of honor killing and rape. In 2009 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that a 2002 honor killing constituted gender discrimination. In response, the government introduced a new policy whereby police officers responding to calls for help regarding domestic abuse would be held legally responsible should any subsequent abuse occur.

Armenia (2010)

Capital: Yerevan

Population: 3,097,000

Political Rights Score: 6

Civil Liberties Score: 4

Status: Partly Free

Overview

The ruling Republican Party won municipal elections in the capital in May 2009, securing a majority of council seats and confirmation of the appointed incumbent as mayor. International observers alleged widespread fraud, and opposition parties refused to recognize the results. Meanwhile, police abuses committed during the violence that followed the 2008 presidential election remained largely unpunished, and a number of opposition supporters who were arrested during the 2008 crackdown were still behind bars at year’s end.

After a short period of independence amid the turmoil at the end of World War I, Armenia was divided between Turkey and the Soviet Union by 1922. Most of the Armenians in the Turkish portion were killed or driven abroad during the war and its aftermath, but those in the east survived Soviet rule. The Soviet republic of Armenia declared its independence in 1991, propelled by a nationalist movement that had gained strength during the tenure of reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s. The movement had initially focused on demands to transfer the substantially ethnic Armenian region of Nagorno-Karabakh from Azerbaijan to Armenia; Nagorno-Karabakh was recognized internationally as part of Azerbaijan, but by the late 1990s, it was held by ethnic Armenian forces who claimed independence.Prime Minister Robert Kocharian, the former president of Nagorno-Karabakh, was elected president of Armenia in 1998.

The country was thrust into a political crisis on October 27, 1999, when five gunmen stormed into the National Assembly and assassinated Prime Minister Vazgen Sarkisian, assembly speaker Karen Demirchian, and several other senior officials. The leader of the gunmen, Nairi Hunanian, maintained that he and the other assailants had acted alone in an attempt to incite a popular revolt against the government. Allegations that Kocharian or members of his inner circle had orchestrated the shootings prompted opposition calls for the president to resign. Citing a lack of evidence, however, prosecutors did not press charges against Kocharian, who gradually consolidated his power during the following year.

In 2003, Kocharian was reelected in a presidential vote that was widely regarded as flawed, with the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) alleging widespread ballot-box stuffing. During the runoff, authorities placed more than 200 opposition supporters in administrative detention for over 15 days; they were sentenced on charges of hooliganism and participation in unsanctioned demonstrations. The Constitutional Court upheld the election results, but it proposed holding a “referendum of confidence” on Kocharian within the next year; Kocharian rejected the proposal. Opposition parties boycotted subsequent sessions of the National Assembly, and police violently dispersed protests mounted in the spring of 2004 over the government’s failure to redress the problems of the 2003 vote.

The Republican Party of Armenia (HHK)—the party of Prime Minister Serzh Sarkisian, a close Kocharian ally—won 65 of 131 seats in the May 2007 National Assembly elections. Two other pro-presidential parties took a total of 41 seats, giving the government a clear majority. Opposition parties suffered from disadvantages regarding media coverage and the abuse of state resources ahead of the vote.

The 2008 presidential election was held on February 19. Five days after the balloting, the Central Election Commission announced that Sarkisian had won 52.8 percent and the main opposition candidate, former president Levon Ter-Petrosian, had taken 21.5 percent. The results, which the opposition disputed, allowed Sarkisian to avoid a runoff vote. Peaceful opposition demonstrations that began on February 21 turned violent a week later when the police engaged the protesters. According to the OSCE, 10 people were killed and more than 200 were injured during the clashes. Outgoing president Kocharian declared a 20-day state of emergency, and more than 100 people were arrested in the wake of the upheaval. The OSCE’s final observation report stated that the electoral deficiencies had “resulted primarily from a lack of sufficient will to implement legal provisions effectively and impartially.”

By the end of 2009, little had been done to punish police officers for abuse during the 2008 post election violence. Though there were reportedly hundreds of internal inquiries, only a handful of officers were charged with using excessive force. In late 2009, investigators for the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) criticized the results of an Armenian parliamentary inquiry, which found that the crackdown on the post election protests had been “by and large legitimate and adequate.” A general amnesty bill passed in June freed 30 protesters, but more than a dozen reportedly remained in prison at year’s end.

Municipal elections for Yerevan were held in May 2009. The HHK secured 35 of 65 seats in the city council, meaning the appointed HHK incumbent was reinstated as mayor. Opposition parties refused to recognize the results, accusing the ruling party of fraud. Observers with the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) reported witnessing “egregious violations,” and the Council of Europe similarly cited “serious deficiencies.”

Political Rights and Civil Liberties

Armenia is not an electoral democracy. The unicameral National Assembly is elected for four-year terms, with 90 seats chosen by proportional representation and 41 through races in single-member districts. The president is elected by popular vote for up to two five-year terms. However, elections since the 1990s have been marred by serious irregularities. The May 2007 parliamentary vote was described by the OSCE as an improvement, albeit flawed, over previous polls, but the 2008 presidential election was seriously marred by problems with the vote count, a biased and restricted media environment, and the abuse of administrative resources in favor of ruling party candidate Serzh Sarkisian. The Yerevan municipal elections held in May 2009 were the first in which the capital’s mayor was indirectly elected rather than appointed by the president. They also suffered from serious violations, though international observers claimed that the fraud did not jeopardize the overall legitimacy of the results.

Bribery and nepotism are reportedly common among government officials, who are rarely prosecuted or removed for abuse of office. Corruption is also believed to be a serious problem in law enforcement. Armenia was ranked 120 out of 180 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index.

There are limits on press freedom in Armenia. The authorities use informal pressure to maintain control over broadcast outlets, the chief source of news for most Armenians. State-run Armenian Public Television is the only station with nationwide coverage, and the owners of most private channels have close government ties. The independent television company A1+ continued to be denied a license in 2009 despite a 2008 ruling in its favor by the European Court of Human Rights. Libel is considered a criminal offense, and violence against journalists is a problem. The Helsinki Committee of Armenia reported that attacks on journalists increased in both frequency and cruelty in 2009. Among other assaults during the year, Argishti Kivirian, the founding editor of the news website Armenia Today, was severely beaten in late April, and a week later two assailants attacked Nver Mnatsakanian, a television journalist and commentator. Amnesty International reported that independent media outlets that covered the political activities of the opposition were often harassed. The authorities generally do not interfere with internet access.

Freedom of religion is generally respected, though the dominant Armenian Apostolic Church enjoys certain exclusive privileges, and members of minority faiths sometimes face societal discrimination. At the end of 2009, there were 76 Jehovah’s Witnesses serving prison terms for refusing to participate in either military service or the military-administered alternative service for conscientious objectors.

The government generally does not restrict academic freedom. Public schools are required to display portraits of the president and the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, and to teach the Church’s history.

In the aftermath of the 2008 post election violence, the government imposed restrictions on freedom of assembly. The majority of opposition requests to hold demonstrations in 2009 were rejected, and the authorities allegedly restricted road access to the capital ahead of planned opposition rallies. Police also reportedly continued to use force to disperse some opposition gatherings. In December, four police officers were convicted of abusing protesters in the 2008 clashes, but they avoided jail time under a general amnesty enacted in June.

Registration requirements for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are cumbersome and time-consuming. Some 3,000 NGOs are registered with the Ministry of Justice, although many are not active in a meaningful way. While the constitution provides for the right to form and join trade unions, labor organizations are weak and relatively inactive in practice.

The judicial branch is subject to political pressure from the executive branch and suffers from considerable corruption. Police make arbitrary arrests without warrants, beat detainees during arrest and interrogation, and use torture to extract confessions. Prison conditions in Armenia are poor, and threats to prisoner health are significant.

Although members of the country’s tiny ethnic minority population rarely report cases of overt discrimination, they have complained about difficulties in receiving education in their native languages. Members of the Yezidi community have sometimes reported discrimination by police and local authorities.

Citizens have the right to own private property and establish businesses, but an inefficient and often corrupt court system and unfair business competition hinder such activities. Key industries remain in the hands of so-called oligarchs and influential cliques who received preferential treatment in the early stages of privatization.

According to the current election code, women must account for 15 percent of a party’s candidate list for the parliament’s proportional-representation seats and occupy every 10th position on the list. Women currently hold 12 of the 131 National Assembly seats. Domestic violence and trafficking in women and girls for the purpose of prostitution are believed to be serious problems. Though homosexuality was decriminalized in 2003, homosexual individuals still face violence and persecution.

Methodology

Introduction | Methodology | Checklist Questions and Guidelines | Selected Sources | Survey Team | Acknowledgments | Country Reports | Tables and Charts | Essays

INTRODUCTION

The Freedom in the World survey provides an annual evaluation of the state of global freedom as experienced by individuals. The survey measures freedom—the opportunity to act spontaneously in a variety of fields outside the control of the government and other centers of potential domination—according to two broad categories: political rights and civil liberties. Political rights enable people to participate freely in the political process, including the right to vote freely for distinct alternatives in legitimate elections, compete for public office, join political parties and organizations, and elect representatives who have a decisive impact on public policies and are accountable to the electorate. Civil liberties allow for the freedoms of expression and belief, associational and organizational rights, rule of law, and personal autonomy without interference from the state.

The survey does not rate governments or government performance per se, but rather the real-world rights and freedoms enjoyed by individuals. Thus, while Freedom House considers the presence of legal rights, it places a greater emphasis on whether these rights are implemented in practice. Furthermore, freedoms can be affected by government officials, as well as by nonstate actors, including insurgents and other armed groups.

Freedom House does not maintain a culture-bound view of freedom. The methodology of the survey is grounded in basic standards of political rights and civil liberties, derived in large measure from relevant portions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These standards apply to all countries and territories, irrespective of geographical location, ethnic or religious composition, or level of economic development. The survey operates from the assumption that freedom for all peoples is best achieved in liberal democratic societies.

The survey includes both analytical reports and numerical ratings for 193 countries and 16 select territories.[1] Each country and territory report includes an overview section, which provides historical background and a brief description of the year’s major developments, as well as a section summarizing the current state of political rights and civil liberties. In addition, each country and territory is assigned a numerical rating—on a scale of 1 to 7—for political rights and an analogous rating for civil liberties; a rating of 1 indicates the highest degree of freedom and 7 the lowest level of freedom. These ratings, which are calculated based on the methodological process described below, determine whether a country is classified as Free, Partly Free, or Not Free by the survey.

The survey findings are reached after a multilayered process of analysis and evaluation by a team of regional experts and scholars. Although there is an element of subjectivity inherent in the survey findings, the ratings process emphasizes intellectual rigor and balanced and unbiased judgments.

HISTORY OF THE SURVEY

Freedom House’s first year-end reviews of freedom began in the 1950s as the Balance Sheet of Freedom. This modest report provided assessments of political trends and their implications for individual freedom. In 1972, Freedom House launched a new, more comprehensive annual study called The Comparative Study of Freedom. Raymond Gastil, a Harvard-trained specialist in regional studies from the University of Washington in Seattle, developed the survey’s methodology, which assigned political rights and civil liberties ratings to 151 countries and 45 territories and—based on these ratings—categorized them as Free, Partly Free, or Not Free. The findings appeared each year in Freedom House’s Freedom at Issue bimonthly journal (later titled Freedom Review). The survey first appeared in book form in 1978 under the title Freedom in the World and included short, explanatory narratives for each country and territory rated in the study, as well as a series of essays by leading scholars on related issues. Freedom in the World continued to be produced by Gastil until 1989, when a larger team of in-house survey analysts was established. In the mid-1990s, the expansion of Freedom in the World’s country and territory narratives demanded the hiring of outside analysts—a group of regional experts from the academic, media, and human rights communities. The survey has continued to grow in size and scope; the 2009 edition is the most exhaustive in its history.

RESEARCH AND RATINGS REVIEW PROCESS

This year’s survey covers developments from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2008, in 193 countries and 16 territories. The research and ratings process involved 40 analysts and 17 senior-level academic advisers—the largest number to date. The 11 members of the core research team headquartered in New York, along with 29 outside consultant analysts, prepared the country and territory reports. The analysts used a broad range of sources of information—including foreign and domestic news reports, academic analyses, nongovernmental organizations, think tanks, individual professional contacts, and visits to the region—in preparing the reports.

The country and territory ratings were proposed by the analyst responsible for each related report. The ratings were reviewed individually and on a comparative basis in a series of six regional meetings—Asia-Pacific, Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Western Europe—involving the analysts, academic advisors with expertise in each region, and Freedom House staff. The ratings were compared to the previous year’s findings, and any major proposed numerical shifts or category changes were subjected to more intensive scrutiny. These reviews were followed by cross-regional assessments in which efforts were made to ensure comparability and consistency in the findings. Many of the key country reports were also reviewed by the academic advisors.

CHANGES TO THE 2009 EDITION OF FREEDOM IN THE WORLD

The survey’s methodology is reviewed periodically by an advisory committee of political scientists with expertise in methodological issues. Over the years, the committee has made a number of modest methodological changes to adapt to evolving ideas about political rights and civil liberties. At the same time, the time series data are not revised retroactively, and any changes to the methodology are introduced incrementally in order to ensure the comparability of the ratings from year to year.

For the 2009 edition of the survey, one change was made to the checklist question guidelines (the checklist questions are used by the analysts when scoring each of their countries, while the guidelines—in the form of bulleted sub-questions—provide general guidance to the analysts about issues they should consider when scoring each checklist question). Civil liberties question G.1 and two of its sub-questions were reworded slightly to include the possible effect of nonstate actors on freedom of travel or choice of residence, employment, or institution of higher education; previously, the questions focused more on state actors. (The complete checklist questions and guidelines appear in the "Checklist Questions and Guidelines" document.) In addition, a change was made in the criteria for determining whether a country is classified as an electoral democracy; in addition to the previous requirement of a subtotal score of 7 or better (out of a possible total score of 12) for political rights sub-category A (Electoral Process), a country must now also receive an overall political rights score of 20 or better (out of a possible total score of 40). Finally, South Ossetia was added as a separate disputed territory after Russia’s August 2008 invasion and subsequent political and economic takeover.

RATINGS PROCESS

(NOTE: see the complete checklist questions and keys to political rights and civil liberties ratings and status in the "Checklist Questions and Guidelines" document.)

Scores – The ratings process is based on a checklist of 10 political rights questions and 15 civil liberties questions. The political rights questions are grouped into three subcategories: Electoral Process (3 questions), Political Pluralism and Participation (4), and Functioning of Government (3). The civil liberties questions are grouped into four subcategories: Freedom of Expression and Belief (4 questions), Associational and Organizational Rights (3), Rule of Law (4), and Personal Autonomy and Individual Rights (4). Scores are awarded to each of these questions on a scale of 0 to 4, where a score of 0 represents the smallest degree and 4 the greatest degree of rights or liberties present. The political rights section also contains two additional discretionary questions: question A (For traditional monarchies that have no parties or electoral process, does the system provide for genuine, meaningful consultation with the people, encourage public discussion of policy choices, and allow the right to petition the ruler?) and question B (Is the government or occupying power deliberately changing the ethnic composition of a country or territory so as to destroy a culture or tip the political balance in favor of another group?). For additional discretionary question A, a score of 1 to 4 may be added, as applicable, while for discretionary question B, a score of 1 to 4 may be subtracted (the worse the situation, the more that may be subtracted). The highest score that can be awarded to the political rights checklist is 40 (or a total score of 4 for each of the 10 questions). The highest score that can be awarded to the civil liberties checklist is 60 (or a total score of 4 for each of the 15 questions).

The scores from the previous survey edition are used as a benchmark for the current year under review. In general, a score is changed only if there has been a real world development during the year that warrants a change (e.g., a crackdown on the media, the country’s first free and fair elections) and is reflected accordingly in the narrative.

In answering both the political rights and civil liberties questions, Freedom House does not equate constitutional or other legal guarantees of rights with the on-the-ground fulfillment of these rights. While both laws and actual practices are factored into the ratings decisions, greater emphasis is placed on the latter.

For states and territories with small populations, the absence of pluralism in the political system or civil society is not necessarily viewed as a negative situation unless the government or other centers of domination are deliberately blocking its operation. For example, a small country without diverse political parties or media outlets or significant trade unions is not penalized if these limitations are determined to be a function of size and not overt restrictions.

Political Rights and Civil Liberties Ratings – The total score awarded to the political rights and civil liberties checklist determines the political rights and civil liberties rating. Each rating of 1 through 7, with 1 representing the highest and 7 the lowest level of freedom, corresponds to a range of total scores (see tables 1 and 2 in the "Checklist Questions and Guidelines" document).

Status of Free, Partly Free, Not Free – Each pair of political rights and civil liberties ratings is averaged to determine an overall status of “Free,” “Partly Free,” or “Not Free.” Those whose ratings average 1.0 to 2.5 are considered Free, 3.0 to 5.0 Partly Free, and 5.5 to 7.0 Not Free (see table 3 in the "Checklist Questions and Guidelines" document). The designations of Free, Partly Free, and Not Free each cover a broad third of the available scores. Therefore, countries and territories within any one category, especially those at either end of the category, can have quite different human rights situations. In order to see the distinctions within each category, a country or territory’s political rights and civil liberties ratings should be examined. For example, countries at the lowest end of the Free category (2 in political rights and 3 in civil liberties, or 3 in political rights and 2 in civil liberties) differ from those at the upper end of the Free group (1 for both political rights and civil liberties). Also, a designation of Free does not mean that a country enjoys perfect freedom or lacks serious problems, only that it enjoys comparably more freedom than Partly Free or Not Free (or some other Free) countries.

Indications of Ratings and/or Status Changes – Each country or territory’s political rights rating, civil liberties rating, and status is included in a statistics section that precedes each country or territory report. A change in a political rights or civil liberties rating since the previous survey edition is indicated with a symbol next to the rating that has changed. A brief ratings change explanation is included in the statistics section.

Trend Arrows – Positive or negative developments in a country or territory may also be reflected in the use of upward or downward trend arrows. A trend arrow is based on a particular development (such as an improvement in a country’s state of religious freedom), which must be linked to a score change in the corresponding checklist question (in this case, an increase in the score for checklist question D2, which covers religious freedom). However, not all score increases or decreases warrant trend arrows. Whether a positive or negative development is significant enough to warrant a trend arrow is determined through consultations among the report writer, the regional academic advisers, and Freedom House staff. Also, trend arrows are assigned only in cases where score increases or decreases are not sufficient to warrant a ratings change; thus, a country cannot receive both a ratings change and a trend arrow during the same year. A trend arrow is indicated with an arrow next to the name of the country or territory that appears before the statistics section at the top of each country or territory report. A brief trend arrow explanation is included in the statistics section.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF EACH POLITICAL RIGHTS AND CIVIL LIBERTIES RATING

POLITICAL RIGHTS

Rating of 1 – Countries and territories with a rating of 1 enjoy a wide range of political rights, including free and fair elections. Candidates who are elected actually rule, political parties are competitive, the opposition plays an important role and enjoys real power, and minority groups have reasonable self-government or can participate in the government through informal consensus.

Rating of 2 – Countries and territories with a rating of 2 have slightly weaker political rights than those with a rating of 1 because of such factors as some political corruption, limits on the functioning of political parties and opposition groups, and foreign or military influence on politics.

Ratings of 3, 4, 5 – Countries and territories with a rating of 3, 4, or 5 include those that moderately protect almost all political rights to those that more strongly protect some political rights while less strongly protecting others. The same factors that undermine freedom in countries with a rating of 2 may also weaken political rights in those with a rating of 3, 4, or 5, but to an increasingly greater extent at each successive rating.

Rating of 6 – Countries and territories with a rating of 6 have very restricted political rights. They are ruled by one-party or military dictatorships, religious hierarchies, or autocrats. They may allow a few political rights, such as some representation or autonomy for minority groups, and a few are traditional monarchies that tolerate political discussion and accept public petitions.

Rating of 7 – Countries and territories with a rating of 7 have few or no political rights because of severe government oppression, sometimes in combination with civil war. They may also lack an authoritative and functioning central government and suffer from extreme violence or warlord rule that dominates political power.

CIVIL LIBERTIES

Rating of 1 – Countries and territories with a rating of 1 enjoy a wide range of civil liberties, including freedom of expression, assembly, association, education, and religion. They have an established and generally fair system of the rule of law (including an independent judiciary), allow free economic activity, and tend to strive for equality of opportunity for everyone, including women and minority groups.

Rating of 2 – Countries and territories with a rating of 2 have slightly weaker civil liberties than those with a rating of 1 because of such factors as some limits on media independence, restrictions on trade union activities, and discrimination against minority groups and women.

Ratings of 3, 4, 5 – Countries and territories with a rating of 3, 4, or 5 include those that moderately protect almost all civil liberties to those that more strongly protect some civil liberties while less strongly protecting others. The same factors that undermine freedom in countries with a rating of 2 may also weaken civil liberties in those with a rating of 3, 4, or 5, but to an increasingly greater extent at each successive rating.

Rating of 6 – Countries and territories with a rating of 6 have very restricted civil liberties. They strongly limit the rights of expression and association and frequently hold political prisoners. They may allow a few civil liberties, such as some religious and social freedoms, some highly restricted private business activity, and some open and free private discussion.

Rating of 7 – Countries and territories with a rating of 7 have few or no civil liberties. They allow virtually no freedom of expression or association, do not protect the rights of detainees and prisoners, and often control or dominate most economic activity.

Countries and territories generally have ratings in political rights and civil liberties that are within two ratings numbers of each other. For example, without a well-developed civil society, it is difficult, if not impossible, to have an atmosphere supportive of political rights. Consequently, there is no country in the survey with a rating of 6 or 7 for civil liberties and, at the same time, a rating of 1 or 2 for political rights.

ELECTORAL DEMOCRACY DESIGNATION

In addition to providing numerical ratings, the survey assigns the designation “electoral democracy” to countries that have met certain minimum standards. In determining whether a country is an electoral democracy, Freedom House examines several key factors concerning the last major national election or elections.

To qualify as an electoral democracy, a state must have satisfied the following criteria:

1. A competitive, multiparty political system;

2. Universal adult suffrage for all citizens (with exceptions for restrictions that states may legitimately place on citizens as sanctions for criminal offenses);

3. Regularly contested elections conducted in conditions of ballot secrecy, reasonable ballot security, and in the absence of massive voter fraud, and that yield results that are representative of the public will;

4. Significant public access of major political parties to the electorate through the media and through generally open political campaigning.

The numerical benchmark for a country to be listed as an electoral democracy is a subtotal score of 7 or better (out of a possible total score of 12) for the political rights checklist subcategory A (the three questions on Electoral Process) and an overall political rights score of 20 or better (out of a possible total score of 40). In the case of presidential/parliamentary systems, both elections must have been free and fair on the basis of the above criteria; in parliamentary systems, the last nationwide elections for the national legislature must have been free and fair. The presence of certain irregularities during the electoral process does not automatically disqualify a country from being designated an electoral democracy. A country cannot be an electoral democracy if significant authority for national decisions resides in the hands of an unelected power, whether a monarch or a foreign international authority. A country is removed from the ranks of electoral democracies if its last national election failed to meet the criteria listed above, or if changes in law significantly eroded the public’s possibility for electoral choice.

Freedom House’s term “electoral democracy” differs from “liberal democracy” in that the latter also implies the presence of a substantial array of civil liberties. In the survey, all Free countries qualify as both electoral and liberal democracies. By contrast, some Partly Free countries qualify as electoral, but not liberal, democracies.

[1]These territories are selected based on their political significance and size. Freedom House divides territories into two categories: related territories and disputed territories. Related territories consist mostly of colonies, protectorates, and island dependencies of sovereign states that are in some relation of dependency to that state, and whose relationship is not currently in serious legal or political dispute. Disputed territories are areas within internationally recognized sovereign states whose status is in serious political or violent dispute, and whose conditions differ substantially from those of the relevant sovereign states. They are often outside of central government control and characterized by intense, longtime, and widespread insurgency or independence movements that enjoy popular support. Generally, the dispute faced by a territory is between independence for the territory or domination by an established state. The decision to identify Nagorno-Karabakh with the two independent countries of Armenia and Azerbaijan reflects the fact that both claim authority over the territory, as well as the fact that Armenia enjoys de facto control over it. This two-country designation is not intended to be an endorsement of Armenian claims over Nagorno-Karabakh.

All items on this site are ©Freedom House, Inc. • All Rights Reserved

Questions? Comments? Contact info@freedomhouse.org

.