Again came April; and from everywhere and by all possible and impossible forms of communication my dear fellow Armenians have begun their annual lamentations that the Turks killed them. I do not know what Genocide hysteria will bring in the future, but I know what it has brought today.

Again came April; and from everywhere and by all possible and impossible forms of communication my dear fellow Armenians have begun their annual lamentations that the Turks killed them. I do not know what Genocide hysteria will bring in the future, but I know what it has brought today.

Everywhere we are seen as a pitiful, broken, morally and psychologically oppressed and massacred and impotent community, which for just those reasons is not capable of self-governing itself or have democracy.

The reconstruction of events that occurred close to one-hundred years ago is a complex process if, of course, you are skilled in the intellectual processes of critique and analysis. If you are not, then it is very easy. You simply allow your teachers and the authorities to drill their ideas into you, and then you have full knowledge. . .

It is natural for the majority to adopt this brainwashing - it is the easier way out. After all, who would feel like wasting precious time thinking for themselves when those whom the Politburo has already designated as wise, intelligent and knowledgeable have already spent and are spending much time addressing those issues?

It is an illness not limited to us - Armenians. Instead of elevating the spirit of victory like the Americans, British, Russians, and many others do, our (and Jewish) government inculcates us with the images of massacre and genocide. That is done with the purpose of not noticing the genocide taking place at this very moment - the emigration that reaches alarming proportions, the erosion and universal demoralization in the Diaspora and the Homeland.

Armenians worldwide do not mourn the memories of those being killed now by the self-designated mob, or the fate of our fellow Armenians who are murdered or degraded daily in Russia, or the emigrants who try in every way to stay in Europe or the US. The latter have opted to endure a multitude of humiliations, but under no circumstances wish to return to the Homeland, where the population is steadily declining.

We have consigned to naught and oblivion the thousands of our imprisoned fellow Armenians the world over. A significant number of them are slandered and helpless, while our so-called government has not taken a single step nor is prepared to take any measures to protect them.

It is allowed to degrade, imprison, violently assault, spiritually and physically oppress, and kill our own fellow Armenians. Directly or indirectly, all of our failures are explained through Turks and Ottomanism, through the damages incurred by their actions - but never as a result of Bolshevism, Communism, KGB-ism, the culture of under-handedness and Oligarchism, tribal egocentrism, fanaticism, and worst of all, through provincial obscurantism and ignorance.

The worldwide pursuit of the century old phantoms to escape the gravest issues and responsibilities of the present time has become our only business.

Washington, D.C., 16 April 2009

.

Lawsuit Against U.S. Federal Reserve Seeks Armenian Gold Looted by Turkey By Harut Sassounian

Lawsuit Against U.S. Federal Reserve Seeks Armenian Gold Looted by Turkey By Harut Sassounian

Comments by Sukru Server Aya In Blue

The Glendale-based nonprofit Center for Armenian Remembrance (CAR) sued the U.S. Federal Reserve on March 4, seeking information on its acquisition of a large amount of Armenian gold looted by the Ottoman government in 1915.

CAR filed the lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act. The gold, originally valued at 5 million Turkish gold liras ($22 million dollars), is now estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York recently claimed they have no records of any Armenian gold in their possession.

It was not easy to trace the circumstances under which the Armenian-owned gold was transferred from Istanbul to the United States almost a century ago. The results of our research on the convoluted series of transactions are summarized below:

The Ottoman government had seized the gold and other valuables belonging to Armenians deported and killed in the 1915 genocide, expropriating their bank accounts and safe deposit boxes. The Ottoman Liquidation Commission used a complex set of bank transfers to hide the trail of this “blood money.” The Turkish Treasury placed the looted Armenian gold initially in the German Deutschebank in Istanbul. In 1916, the gold was transferred to the Bleichroeder Bank in Vienna, and from there moved to the Reichsbank (German Central Bank) in Berlin and was deposited in the account of Ottoman Public Debt.

Comment: There is no record anywhere that the Ottoman Government seized gold or other valuables belonging to Armenians or expropriating bank accounts. US Consul L. Davis speaks of Armenians leaving cash with him to be collected later. . . .

Protestant and Catholic Armenians were permitted to return and repossess what they had left behind. After the 30.10.1918 Mudros Treaty about 200 – 300.000 Armenians from Syria returned under British-French occupation to their homes. These left Turkey in late 1921 with their own will, when French armies pulled out! We know that in 1917 when the Tsarist Russian’s refugee ships anchored in the Bosporus, Greek and Armenian grocers were selling loaf of bread and bottle of water for a golden ring! Practically there were no Turkish grocers (or other artisans) and about 180.000 Armenians on the Western costs were never touched on any subject!

According to Efraim & Inari Karsh, (ISBN 0-674-00541-4) “Empires of the Sand”, p.116&134, Ottomans borrowed on Sept. 30th, 1914 from Germany 5 millions Turkish Gold liras at 6% interest, which was paid in several installments so that Turks could enter War. We also have records that Ottomans before WW1 owed a total of 142.2 millions Sterling to foreign creditors and 53% of this was payable to France, 21% to Germany and 14% to Britain. These debts were liquidated after the Lausanne Peace Treaty with the agreement dated 24.7.1923 and paid by the Turkish Republic to creditor states. To think that the Ottomans who could not even pay the salaries of army officers had a surplus of (any) GOLD and sent it to Germany is a fantasy that suits great “treasury hunt dreamers”! The demands of indemnities of US Companies and persons from the Turkish Republic were treated under a separate agreement concluded with exchange of letters in 1937 and paid thereafter with incurred interests. So, legally there is nothing that any State or Entity can demand from the Republic of Turkey for Ottoman debts (or assets) !

At the end of World War I, when the Allied Powers demanded reparations from Germany and its Ottoman Turkish ally, German officials had no choice but to comply with that request, agreeing to turn over to the Allies the Armenian gold held by the Reichsbank. Accordingly, the expropriated Armenian gold was transferred to France and Great Britain in 1921.

I have no knowledge about the gold of Reichsbank, its transfer or where it came from!

A subsequent British document confirms the true ownership of this gold. On Sept. 26 1924, leaders of the two main opposition parties in Great Britain, Liberal Party leader and former Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, and Conservative Party leader and future Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, sent a memorandum to Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald pleading for British assistance to Armenians in view of their support for the Allied cause and the great suffering they endured during World War I. The two British leaders argued that “the sum of 5 million pounds (Turkish gold) deposited by the Turkish Government in Berlin in 1916, and taken over by the Allies after the Armistice, was in large part (perhaps wholly) Armenian money. After the enforced deportation of the Armenians in 1915, their bank accounts, both current and deposit, were transferred by order to the State Treasury at Constantinople. This fact enabled the Turks to send five million sterling to the Reichsbank, Berlin, in exchange for a new issue of notes.”

Subsequently, instead of returning the Armenian gold to its original owners, Britain and France sold it to the United States government through J.P. Morgan Bank in Paris, by exchanging it for U.S. Treasury Certificates.

On Jan. 29, 1925, Senator William H. King submitted Resolution 319 to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee demanding that the looted gold be “set aside in trust” for Armenians. The resolution stated: “The Turkish Government had arbitrarily seized and transferred to the Turkish treasury all bank accounts, both current and deposit, belonging to Armenians, by which Armenian gold in the sum of 5 million Turkish pounds, amounting to $22,450,000, was transferred to the Turkish treasury, which gold was afterwards deposited by the Turkish Government in the Reichsbank at Berlin… Said deposit of Armenian gold in the Reichsbank at Berlin was by article 259 of the Treaty of Versailles transferred and surrendered to the principal allied and associated powers, including the United States… Said deposit in equity and right belongs to the Armenians from whom the same was seized, or to their legal representatives… Said deposit should be set aside in trust to be hereafter paid over to the persons from whom said gold was seized, or to their lawful representatives.

Comment: Dr. Fridthjof Nansen, Gen. Secretary of League of Nations, on 21.9.1929 at the 16th Planetary Meeting when speaking on Armenia had confessed that the allies had promised “if you fight with us against the Turks, and if the war ends successfully for us, we promise to give you a national home, liberty and independence”. He further had complained that he went to Armenia but since the Allies did not give money, the projects for recovery were abandoned. Now let us use our logic to evaluate the truth behind many shiny words:

a. By 24.9. 1924 the Lausanne Treaty was over one year old and the British Politicians were “perfectly aware that there was no floating gold searching for pockets”. Britain knew too well that they had abandoned Armenians many times refusing to give them much smaller amounts as credit, and hence this sound like another “ hope in the air” just to cover up the solemn past.

b. As regards Senator King’s report of Jan. 1925, by that time not only the financial matters related to Turkey were settled in 1923, but there was no such indications in the report of General Harbord of 1919, nor in the Near East Relied Report, approved on 22.4.1922. Ambassador Morgenthau was the most capable and trusted man on all money matters. (His son became Secretary of Treasury to Pres. Roosevelt for eleven years). I would ask why none of these persons in bad need of money, never heard of a deposit of 5 millions Sterling or gold in Germany in 1916! How come this was not ever mentioned during the 1919 Paris Conference?

This gold is just a small portion of the billions of dollars of Armenian assets stolen by Turkey and various other countries during and after the Armenian Genocide. The restitution of all looted Armenian assets, wherever they may be, should be one of the highest priorities for those pursuing justice for the horrendous crimes committed against the Armenian nation.

The usual arrogant and slanderous language used by the writer to please the ego of his readers (already voiced in the comments) does not add any seriousness or creditability to this fantasy. An old folk Turkish proverb says: “The hungry hen, dreams of the barn full of barley”!

Sukru S. Aya

.

08 Feb 11

* From the conference chaired by Sukru Elekdag - 19/03/2009

There were many occasions when the Turkish Government could have gone to court in the past against the Armenians, but did not choose to do so. However, it is not too late to resort to litigation against some Armenians, Armenian organizations, and/or publications for slander and hate crimes.

I) Occasions missed by Turks to crush Armenian Aggression in Western countries . .

— December 25, 1933: Archbishop Leon Tourian is assassinated by Dashnaks in his church in New York. The majority of US newspapers, even The New York Times, describes Dashnak party as a gang of terrorists, funded by Nazi and Fascist regimes.

Despite the fact that ARF attempted to kill Atatürk several times during the 1920’s, and that several Dashnaks were hanged in Turkey for plotting, Turkish diplomacy did not pursue any prosecution against ARF in the USA, whose offices are located in Boston, MA.

— 1944: non-Dashnak Armenian Americans publish in New York “Dashnak Collaboration with the Nazi Regime”. Turkey does not ask for a court case for Armenian collaboration with the enemy. Similarly, despite the collaboration between ARF and Nazis in France, Turkish embassy does not protest to the French government. The neighborhood of the young Dashnak members in Décines-Charpieu (Lyon’s suburb) is even named “Dro” — the name of the chief of 812th Armenian battalion of Wermacht.

— Spring 1973: Asbarez, the newspaper of ARF in the Western part of the USA, publishes explicit calls to terrorism against the Turks, which could be a reason for a legal case to be opened under US law. Both Dashnak and non-Dashnak associations of California support Gourgen Yanıkian and condone his use of violence. No court case is filed.

— Winter 1976: In Paris, Ara Toranian starts to publish Hay Baykar/Combat Arménien, a weekly publication supporting the ASALA, as well as ASALA-RM, and sometimes Justice Commandos of Armenian Genocide/Armenian Revolutionary Army (terroristic branch of ARF) as well. Toranian receives no punishment until 1988. The French law punishes any incitement to take arms against the State, or against a part of the population, for up to five years, if the provocation is not followed by acts; and by up to 30 years of jail if the provocation is followed by physical acts. Toranian was sued in 1985-1986 for material help to terrorists; he was sentenced in the first instance, but won after an appeal found some benefit of doubt in the case.

— May 27, 1976: a terrorist of JCAG is killed by the accidental explosion of his bomb; the incident happens in the general quarter of ARF in France, rue Bleue (Blue Street) of Paris. French police seizes documents about the assassination of Turkish ambassadors in Paris and Vienna, as well as other documents regarding the future bombings in İstanbul, on May 28 and June 9, 1977. Turkish embassy files no complaint, despite the obvious hate of ARF for the actual French center-right government, hostility which had resulted in the political fragility of Dashnaks at that time.

— 1980-1986: Haïastan, newspaper of the young French Dashnaks, publishes many articles supporting terrorism, calling to take arms, which could be sufficient reason to have the editorial staff to be sentenced to jail. No complaint is filed, even after the departure of pro-Dashnaks from French socialist government in 1984.

— June 1981: Ara Toranian and his friends occupy the Parisian office of Turkish Airlines. No court case was brought up for disturbing the public order.

— January 1982: Stanford J. Shaw’s office is ransacked by fanatic Armenian -American students, encouraged by Richard G. Hovannisian. Because of this violence, as well as repeated assaults, Prof. Shaw is prevented to teach at the University of California, at least until 1986. No court case against the perpetrators and Prof. Hovannisian was sought. No court case, too, was filed against those who sent death threats to Shaw’s family.

—July 2, 1983: The Armenian Weekly, newspaper of ARF in the Eastern part of the USA, publishes an article supporting the terrorists; More articles in the same vein are published in the issues of August 21, 1983, September 17, December 10, December 24; January 14, 1984, January 21 and January 28. No complaint is filed by Turkish diplomats or by Turkish-American associations, despite the conviction of murderer, Hampig Sassounian to life, in 1984.

— 1983: Harry Derderian, leader of the Armenian National Committee (ANC, branch of ARF in the USA) states to a reporter: “If terrorism is a contributing factor in getting people’s attention, I can go along with it.” (quoted in The Washington Times, August 3, 1983). No court case for incitation to murder was filed.

— 1985: Armenian activists fail to obtain “recognition” in the European Parliament. The Turks consider that the game is over, and Armenian activists are the winners in 1987.

— 1990-1994: several French citizens obtain the condemnation of persons who called them “denialists” in Paris and Lyon’s tribunals. Turkish diplomacy does not use these judgments to sue the Armenian activists who regularly call them “denialists”.

— 1993-1995: “Lewis affair”. No Turkish scholar attempts to support Bernard Lewis; Turkish embassy fails to ask Prof. Lewis to appeal his conviction. In two other matters, judged in 2004 and 2005, the Cour de Cassation (French supreme court) decides that the 1382 article of civil code (used against Bernard Lewis) can never be used to restrict the freedom of speech about individuals.

— 1995-1996: “Lowry affair”. Prof. Heath Lowry (Princeton University), victim of defamation and character assassination, receives no support from Turks.

— 1998-2000: “Veinstein affair”. Prof. Gilles Veinstein, elected at the Collège de France, is defamed in several newspapers, receives death threats in his mail box, and in May of 2000, is even assaulted in Aix-en-Provence. Nobody suggests to Prof. Veinstein to sue those who defamed and assaulted him, or at least to file a complaint against unknown persons for death threats; no financial support is proposed. (He has explained to me the difficulty to pay a good lawyer with his salary).

— April 8, 2000. Fanatic young Armenian-Americans attack the “Turkish Night” in University of South California. Policemen arrive and two Armenians are arrested, but the event is canceled. No complaint against the leaders of this anti-Turkish riot (probably ARF) was filed. It was the last of a long series, which started in 1974.

— Spring, Summer and Fall 2000: Huge Armenian demonstration asking “recognition” by the French Senate. There was almost no Turkish reaction.

— 1st January 2001: Following a reform of the French penal code, the decision to liberate persons sentenced to life is no more taken by the Minister of Justice, but by a judge. Immediately, the lawyers of V. Garbidjian, the butcher of Orly, use this reform to obtain the release of their client. Since the Turkish side replies nothing about claims of “genocide” (unlike during the trial), Garbidjian is set free in April of 2001.

— 2002-2003: A hate campaign of both Dashnaks and non-Dashnaks against Samuel Weems, retired U.S. judge and author of “Armenia. The Secrets of a ChristianTerrorist State”. The attacks include death threats and defamation. No Turkish support or official complaint pursues.

— 2003: former ASALA spokesman Ara Toranian is elected president of Coordination, Council of French Armenian Associations. No letters of complaint are sent to politicians who welcome Mr. Toranian.

— 2007: Ara Toranian publishes on his Web site an article presenting Monte Melkonian as a “national hero”. (Melkonian, leader of ASALA until 1983, then of ASALA-RM, was sentenced by Paris tribunal to 4 years of jail for terroristic activities, including illegal storing of weapons and explosives, and served more than three years before to be expelled from French territory.) No reaction.

— April 24, 2009: Ara Toranian calls his “compatriots” to “return to the activism of 1975-1980 years”. No reaction.

— November 2009: Ara Toranian publishes in his newspaper an article of Monte Melkonian, and at least one sentence could have been sufficient to sue him in court for offense to a judgment. Indeed, Mr. Toranian wrote that Melkonian “stopped terrorism” in 1983: Melkonian was sentenced for terroristic activities which happened in 1983-1985. However, no complaint is filed. It is now too late to sue him.

II) The lessons of Some Trials in Western Countries:

A) Trials of Armenian terrorists in Switzerland and in France, during the 1980’s

— The Mardiros Jamgotchian trial (1981)

On June 9, 1981, Mardiros Jamgotchian, an ASALA terrorist, assassinates Mehmet Savaş Yergüz, secretary of Turkish general consul in Geneva. Mardiros Jamgotchian is arrested by Swiss police and brought to court at the end of 1981.

Mardiros Jamgotchian’s defense uses mainly the “genocide” claims as an excuse for the crime. Among the witnesses testifying for the terrorist, there are the “historians” Jean-Marie Carzou (who called a return of Armenian terrorism in a speech of 1972) and Yves Ternon (from 1974 to 2008, a columnist in Haratch, a daily edited by the sympathizers of ARF in Paris). Turkey sends no scholars to challenge the lies of these “scholars”, despite the fact that Türkkaya Ataöv, Salâhi R. Sonyel, Bilâl Şimşir and Esat Uras had already published serious studies on the Armenian issue, and despite the first scholarly symposium organized in Turkey about Armenian issue, ironically in June 1981. Gwynne Dyer, Bernard Lewis and Stanford J. Shaw are not solicited.

Similarly, nobody recalls that one of the lawyers of the ASALA terrorist, Patrick Devedjian, was a member of a far- right group in the 1960′s. This group was vehemently racist, anti-Semitic, and used physical violence; It was outlawed by the French government in the fall of 1968, after a bombing was perpetrated by these fanatics. (Until 2006, Mr. Devedjian refused to express any regret for his past in the violent far right movement.)

As a result of Turkish passivity, Mardiros Jamgotchian was sentenced to only 15 years of jail (the prosecutor had asked for a life sentence), and he was released as early as 1991.

— The Max Hraïr Kilndjian trial (1982)

In February 1980, the Turkish ambassador in Switzerland was the victim of an attempted murder by JCAG. Suspected to be the criminal, because several testimonies, French Dashnak Max Hraïr Kilndjian was arrested and indicted by French authorities. The investigation and the case lasted two years: 1980-1982. Except for a few statements, Turkey showed little reaction. The witnesses of the incident were threatened to death, and nobody, not even MİT, proposed to protect them from Geneva to Aix-en-Provence, where Max Hraïr Kilndjian is prosecuted and tried. As a result, only one witness had the courage to appear in front of the court in 1982. Consequently, Max Hraïr Kildjian’s lawyers were successful in having their client not sentenced for attempt of murder, but only as an accessory in the crime, citing lack of evidence.

Secondly, like during the Jamgotchian trial, several self-proclaimed “scholars” deceive a tribunal completely ignorant of Ottoman history. (In the beginning of the trial, the president asked: “Who is Talat Pasha?”) Turkish Government paid a well-known and efficient lawyer from Marseille, but he was alone against the witnesses of defense and the extremely aggressive crowd of Dashnaks within the tribunal, as well as outside the building.

As a result, Max Hraïr Kilndjian is sentenced to two years of jail, and obtains freedom, since he had spent already this time in jail before the trial.

— The trial of attack against Paris Consulate General 1984)

Paris Consulate General of Turkey is attacked by four terrorists of ASALA in September 1981. The Turkish Consul General is seriously wounded and a guard killed. The trial was started in 1984, i.e. after the Orly attack, and at a time when the right-wing opposition criticized the socialist government about the question of terrorism; Thus, the political atmosphere was less in favor of Armenian nationalists and could become in favor of Turks.

This time, Turkey sent Prof. Türkkaya Ataöv and a delegate of Armenian patriarchate of İstanbul; but Armenian nationalists sent many more witnesses, including Jean-Marie Carzou and Yves Ternon, whose services were already used for the Jamgotchian and Kilndjian trials. So, the Turks were not neglectful, but did not show an appropriate level of response. For example, nobody asked to Dr. Paul B. Henze, Dr. Justin McCarthy and Prof. Michael M. Gunter to at least make a written statement.

As a result, the four terrorists were sentenced to seven years of jail, a sentence considered too long by ASALA’s supporters and by Dashnaks, but clearly less than given in several other cases of assaults with death.

— The Orly trial and other court cases of 1985:

This time, the Turkish side was very well organized, sending several witnesses, including Prof. Türkkaya Ataöv and Prof. Mumtaz Soysal. The plaintiffs had three lawyers: two for arguing about the attack itself, and one, the famous Jean Loyrette (who made his firm the best in France), specifically to challenge “genocide” claims.

The lawyers of defense, Jacques Vergès and Patrick Devedjian, did not present the testimonies of Mr. Carzou or Mr. Ternon this time, afraid to seem supporting the worst kind of terrorism.

However, on a purely legal level, the defense had some advantage. Indeed, in 1985 (it changed as early as 1986), French law did not authorize release of the methods of investigation used against terrorists. So, the Direction de la surveillance du territoire (French counter-intelligence and counter-terrorist police service) refrained from exposing all the material in the legal file, being afraid that other terrorists, including members of ASALA, could use such information to prepare future attacks with more safety. As a result, the principal perpetrator of attack, V. Garbidjian, was tried and sentenced as an accessory, not as an assassin (see, for example, the testimony of Gilles Ménage, chief of staff of President François Mitterrand, in the documentary about Jacques Vergès, Advocate of Terror, by Barbet Schröder, 2007; only the French original version is available in DVD).

So, if V. Garbidjian was sentenced to life, it was not only because the majority of the victims killed were non-Turks, but also because the plaintiffs were able to challenge efficiently the “genocide” claims.

Similarly, Jean Loyrette obtained during other trials organized in 1985-1986, that several members of Armenian National Movement (political branch of ASALA until 1983, of ASALA-RM after that date) be sentenced to two to four years of jail for illegal storing of explosives. In a comparable case in Switzerland, 1981, two ASALA terrorists were sentenced to only eighteen months of suspended jail, and immediately released after the trial, to the satisfaction of the terrorists. This time, however, fanatics were very unhappy.

B) Court cases in Switzerland, USA and France during the 2000’s

— The Perinçek trial

Doğu Perinçek wanted to be judged under the regime of the Swiss law that prohibits the challenge of the “Armenian genocide” claims. in some circumstances (and in some circumstances only: despite demands of Armenian nationalists, Prof. Norman Stone was never sued because his article was published in a German-speaking Swiss newspaper). Mr. Perinçek chooses a very good Swiss lawyer, but he leaves him completely alone until a few days before the trial. He gives the lawyer 90 kg of documents, written in Russian. Some Swiss Turks make the heroic effort to translate some of these documents, and discover that they are irrelevant to the Armenian issue.

As a result, Doğu Perinçek is sentenced.

— Jean Schmidt vs David Krikorian

During the elections for US Congress of 2008, the staff of David Krikorian (local leader of ARF, actually independent candidate of the far right, now a Democrat!) uses defamatory posters against Jean Schmidt, republican MP who attempted to be reelected (and was, finally). So, Ms. Schmidt sues Mr. Krikorian, thanks to her personal lawyer as well as to the Turkish American Legal Defense Fund (TALDF), represented for this case by Bruce Fein, international lawyer, specialist of penal law.

Armenian side — this time united, since both Dashnak and non-Dashnak press supported Mr. Krikorian — makes huge efforts, but Mr. Fein stresses, with precise arguments, not only about the defamation itself, but also that there is a scholarly debate about “genocide” allegations.

As a result, electoral commission of Ohio accepted the majority of Ms. Schmidt’s complaints, and declared Mr. Krikorian guilty. We are still waiting to know if Ms. Schmidt will also sue in a civil tribunal.

We also have to wait for the results of the court case of Prof. Guenter Lewy (defended by TALDF) against the Southern Poverty Law Center, but it looks promising.

— The Lyon’s affairs

At the beginning of 2008, before the municipal elections in March, Sırma Oran-Martz, daughter of Baskın Oran, a naturalized French citizen, is presented as a candidate for the Green Party as a candidate for mayor of Villeurbanne (principal town of Lyon’s suburb, with an important Armenian community, entirely led by ARF). Ms. Oran-Martz is pressured to “recognize the genocide”, with increasingly humiliating conditions, and finally renounces her candidacy.

The author of this paper publishes an article on the Web, commenting on the incident, and focusing on the abusive use of the word “denialist” and on the crimes of ARF, from 1890’s to current times. The article is signed, cautiously, only by my initials, . Two days after the publication, my name is revealed on the main French-Armenian Web forum, and I am threatened by death. After a threat by me to file a complaint against him, the majority of messages concerning me are deleted by Ara Toranian, moderator-in-chief of this forum. Following this incident, there is a meeting in Villeurbanne, with Movsès Nissanian, municipal counselor of Villeurbanne and a member of ARF. Mr. Nissanian insults me, saying that I am like “those who sent Jews to Auschwitz”. His words are recorded by the husband of Ms. Oran-Martz, Jean-Patrick Martz.

As a result, two court cases are filed, with the same lawyer, in front of exactly the same Lyon’s tribunal, but with completely different strategies. The legal basis of Sırma Oran’s case against the mayor of Villeurbanne is very slim. The legal basis of my court case against Mr. Nissanian is so strong that even his lawyer does not contest the legal qualification. Despite my repeated suggestions, Ms. Oran refuses absolutely to challenge “genocide” claims. In my court case, when I discover that Mr. Nissanian’s lawyer produced written conclusions of 18 pages focused on “genocide” allegations, I and my lawyer ask, with success, the postponing of the trial; it is postponed from November 3, 2009, to January 5, 2010. During this time, I prepare a text which my lawyer transforms into two appendixes for his arguments: one about ARF (terroristic activities of 1890-1914; terroristic activities of interwar; collaboration with Nazism; terroristic activities of 1975-1993); and one about “genocide claims”, responding to every argument of Mr. Nissanian. I also give my lawyer many articles of the French Dashnak press that supports terrorism.

In addition to these court cases, I also filed a complaint for defamation in the police station of my Parisian district in October 2008, for defamation on the forum of armenews.com As a result of my complaint, Mr. Toranian destroyed his free-access forum entirely, less than seven hours after my complaint.

Not surprisingly, the results are very different. The mayor of Villeurbanne is acquitted on January 5, 2010, and Ms. Oran is sentenced to pay him 1,500 € as a part of his court costs, and 1,500 € as damages for abusive procedure. In the same afternoon, the same tribunal judged Maxime Gauin vs. Movsès Nissanian case. About a half-hour later, the same president who pronounced a severe verdict against Ms. Oran says, “The tribunal does not have to decide between historical thesis.” We have to wait for the verdict on April 27, but one can already notice that Mr. Nissanian has lost his arrogance during the tribunal. He is so afraid to be severely sentenced that he said, in the beginning: “I regret to have used such words”; and in the end: “I reprove these acts of terrorism”.

Another big difference is perceptible in the conditions of the trials. There were many Dashnaks present at both trials. On November 3 (Oran-Martz vs. Bret), they are extremely aggressive and arrogant, and, despite the fact that I was a simple spectator, I am upset by a young Dashnak who was completely hateful. On January 5, there were no young Dashnaks, only old Armenians, who were quiet and showed polite faces. I am able to praise a study of Prof. Yusuf Halaçoğlu and to demonstrate the involvement of ARF leadership in terrorism without provoking a single scream in the room.

Why did this difference exist? Surely not because of a sudden indulgence of Dashnaks for me. More pragmatically, because I wrote a right of reply to Dashnak site (published before the trial), explaining that I would sue anybody who would attack me, and that Mr. Nissanian would be the first to be punished in case of incidents —the nationalist Armenian groups who support him would be next in line.

I sent a last warning one day before the trial. On January 4, Mr. Toranian defamed me on his Web site. I immediately sent an e-mail to him, threatening to sue him, too. One half-hour later, Mr. Toranian answered that to prevent any misunderstanding, he was deleting his article — and he kept his promise.

My court case against Mr. Nissanian, and even the court case of Ms. Oran, had the advantage of showing that the Armenian nationalists of France should refrain from using as an ultimate argument the “recognition” law of January 2001. Indeed, this law is unconstitutional (French Constitution forbids the declarative laws), and a reform of Constitution, voted in 2008, authorizes any person involved in a court case, as plaintiff or as a defendant, to argue of the unconstitutionality of a law if the opposite side uses this law as a main argument.

Even if Mr. Nissanian is severely sentenced and does not appeal such a decision, I have some projects to continue on purely legal ways. Mr. Nissanian is just a municipal counselor, and it would be very unjust that he should remain a long time the single Armenian nationalist of French sued for hate speech.

Conclusion

Both trials of 1980’s and 2000’s demonstrate that court cases are needed, and they are an efficient way to crush Armenian fanatical nationalism, if, and only if:

— An appropriate lawyer is chosen;

— His client is not afraid to challenge “genocide” claims, with scholarly arguments expressed politely submitted, and if he is not afraid to file new complaints in case of new attacks;

— The legal basis is strong.

Armenian nationalism cannot exist without violating the laws of democratic countries, especially the law forbidding defamation. Armenian nationalists understand only the politics of power. As a democratic country herself, Turkey cannot use the methods of rogues — and would probably not want to do it. But Turks should use the excellent means offered by law without hesitation.

http://ataturksocietyuk.com/2011/02/08/%E2%80%9Ccan-the-armenian-issue-be-solved-legally%E2%80%9D-french-historian-maxime-gauin-argues

.

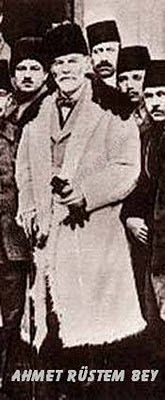

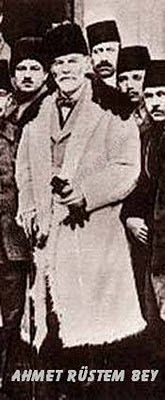

Famous “Water Cure" As Mentioned by Ahmet Rüstem Bey, The Ambassador To The USA

Famous “Water Cure" As Mentioned by Ahmet Rüstem Bey, The Ambassador To The USA

Updated by TruckTurkey

Excerpts From :The Armenian Propaganda in the United States and Ambassador Ahmet Rüstem Bey, The World War and the Turco-Armenian Question, Berne, 1918

Regarding the detachments from the imperial army, several of which have committed excesses here and there, was their conduct so essentially contrary to human nature, and in contrast with that of Western troops? Considering that they were maddened by the action of Armenians, whose cooperation with Russians had decided the fate of more than one battle in favor of the latter! Could it be expected that they would not avenge the misdeeds of the whole Armenian population on fractions of this race, which were perhaps not in actual criminal activity, but which they had reasons to believe guilty of past crimes or ready to commit and felony at the first favorable opportunity? Are they no precedents to “blood lust” at the thought of the savage attacks perpetrated against soldiers’ homes, of the ruins, of the mutilated bodies? Can it be wondered that here and there, soldiers from those detachments should have lost their senses to the extent of carrying out on their adversaries the cruel methods the latter had practiced on themselves? Can the atrocities committed by Wellington’s troops in Spain be recalled? Can we speak of the American Indian Wars, and of the struggle against Filippinos?1

1 There are no atrocities or acts of brigandage that the troops of Wellington did not commit in Spain whenever they met with any resistance in cities.

In the first Indian Wars, American soldiers amused themselves by throwing to one another babies captured from the enemy and catching them on the point of their bayonets. In the Philippines, they resorted to torture in order to elicit information from the natives concerning the movements of Aguinaldo. One form of this torture was the famous “water cure.”

A.Rüstem Bey (Ankara, n.d.). Son of a Polish convert to Islam and an English mother, a member of a well-known British family resident in Istanbul, Ahmed Rüstem (1862–1935) was a career diplomat. As a result of exposing corruption in the Hamidian diplomatic service he was forced to live in exile between 1900 and 1908, being recalled after the revolution. Ahmed Bey was appointed ambassador in Washington in 1914 but was declared persona non grata in September because he retaliated to American criticism of his government’s policies by denouncing the lynching of Blacks in the South and the use of water torture in the Philippines.

The year was 1900

".....The British who occupied Istanbul searched for evidence against the Turkish military and civilian officials they exiled to the island of Malta for 30 months but had to release them when they could not find anything of importance against them. On the other hand, Armenian officials were stressing the fact that they had fought in the ranks of the allied powers and were officially a party to the war so long as they kept the hope of establishing an Armenian State on the Ottoman territory as foreseen in the Treaty of Sevres. However, when the Treaty of Sevres was abrogated they held on to the Armenian Genocide as made up by the Western States. During the 10 years (1979-1989), I served as Ambassador in Washington the activities of the Armenian lobbly to pass a bill from the US Congress accusing Turkey of Armenian Genocide continued incessantly. As a result of these efforts and with the strong support of the Greek lobby, Armenians were able to bring a bill to the floor of the General Council of the House of Representatives. However, in both cases where heated discussions took place the bills were rejected. The rejection of these claims which are seen as undisputed facts by the Armenian lobby, their supporters and a majority of the Americans angered the Armenian circles. Not knowing what to do they wanted to declare the Turkish Ambassador as ´persona non grata´. Deputy Speaker Tony Coelho presented a draft law to the House of Representatives with the signature of 60 deputies with that purpose. This attempt failed. However, the interesting point is that, the incident which led President Wilson to declare Ottoman Ambassador Ahmet Rustem Bey as ´persona non grata´ on 19 September 1914 was also concerned with the Armenian claims. In an article he sent to the ´Washington Star´ Rustem Bey had replied that the American Press had defamated the Ottoman Empire with the groundless claims of oppression on the Armenians and other Christian subjects and that Washington had to learn how to treat the blacks humanely......."

Ahmet Rüstem Bilinski (1862-1935)

The incident which led President Wilson to declare Ottoman Ambassador Ahmet Rustem Bey as 'persona non grata' on 19 September 1914 was concerned with the Armenian claims. In an article he sent to the 'Washington Star' Rustem Bey had replied that the American Press had defamated the Ottoman Empire with the groundless claims of oppression on the Armenians and other Christian subjects and that Washington had to learn how to treat the blacks humanely.

The Washington Post | Washington, D.C. Oct 8, 1914

TURKEY NOT TO FIGHT

Desires Only to Be Let Alone, Says A. Rustem Bey. WILL RETURN TO WASHINGTON Ambassador Sails for Constantinople. Has Not Resigned and Has Not Been Recalled, but Is Going Home on Business -- Stands by Interview Which Offended President.

New York, Oct. 7. -- A. Rustem Bey, Turkish Ambassador to the United States, sailed for Naples on the Italian liner Stampalia, today, after announcing that he stood by the interview he gave in Washington recently and that he intended to return to the United States.

NEW TURKISH ENVOY MOSLEM

Rustem Bey, Assigned to Embassy Here, Recently Embraced Islam Faith.

The Washington Post Washington, D.C. Special to The Washington Post.

Date: Jun 21, 1914

Constantinople, June 20. -- Alfred Rustem Bey de Bilinski, who has just succeeded to the post of Ambassador to the United States, has received widespread commendation in the Turkish newspapers because he recently embraced the Islam faith. He has Polish blood on his father's side, and his mother was Alice Sadison, of all aristocratic British family, which has been settied in Constantinople for two or three generations.

Books by Ahmet Rüstem Bilinski

La Guerre Mondiale et la question turco-armenienne (1918)

La Crise Proche-Orientale et la question des Détroits de Constantinople (1922)

La Paix d'Orient et l'accord franco-turc, "L'Orient et Occident" (1922)

http://maviboncuk.blogspot.com/2006/12/ahmet-rstem-bilinski-1862-1935.html

Direct Link To The Document

Osmanli’da Onurlu Bir Diplomat ve Milli Mücadele’nin Önemli Simasi: Ahmed Rüstem Bey by Dr. Senol KANTARCI

Partially English

Direct Link To The Document

.

“The ARF at 120: A Critical Appreciation” at the New York Hilton Hotel. Featuring historians, economists, political scientists, and activists, this unprecedented panel discussion critically reviewed the ARF’s history and current politics, providing recommendations for the road ahead.

“The ARF at 120: A Critical Appreciation” at the New York Hilton Hotel. Featuring historians, economists, political scientists, and activists, this unprecedented panel discussion critically reviewed the ARF’s history and current politics, providing recommendations for the road ahead.

The panel featured David Grigorian (Senior Fellow, Policy Forum Armenia), Dennis Papazian (Professor Emeritus of History, University of Michigan-Dearborn), Ara Sanjian (Professor of History, University of Michigan-Dearborn), and K.M. Kourken Sarkissian (President, Zoryan Institute), with Dr. Hratch Zadoian (Professor of Political Science, Queens College) serving as moderator. Antranig Kasbarian (chair, ARF Central Committee, Eastern U.S.) served as discussant.

- The ARF’s First 120 Years: A Historian’s Perspective By Ara Sanjian

- ARF: Reflections and refractions: 1988-2010 By Kourken Sarkissian

- Comments by Prof. Dennis Papazian

- ARF and Armenia: How to Withstand the Challenges of the Future? By David Grigorian

- ARF Chair Antranig Kasbarian’s Response to the Papers By Antranig Kasbarian

The ARF’s First 120 Years

A Historian’s Perspective 1

Below are the comments delivered by Ara Sanjian (Professor of History, University of Michigan-Dearborn) at the public forum titled “The ARF at 120: A Critical Appreciation,” held at the New York Hilton Hotel on Nov. 21, 2010.

One constant feature defining the first 120 years of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) has been its incessant activity within the realm of Armenian politics and often in other related domains as well, beyond politics narrowly defined. Historians of almost any post-1890 episode concerning the Armenians inevitably also deal with the ARF, usually directly, or, at the very least, indirectly.

Over these years, the ARF has established a stable following, especially in the post-Genocide Armenian Diaspora. For decades, its influence as a single faction across this—what we may describe as the traditional—Diaspora has far outweighed those of its two, traditional rivals, the Hunchakians and Ramkavars. Moreover, after 1920, the ARF never got reconciled with the narrow Diasporan straightjacket that was imposed upon it by the exigencies of international politics. It tried tirelessly to re-establish its transnational character at every opportunity. Finally, in 1990, it formally returned to the Armenian nation-state, and, since then, it has been trying to re-establish viable roots not only in the Republic of Armenia, but also in the Republic of Mountainous Karabagh (Artsakh), Javakhk, and among Armenians in Russia. It has done so with varying levels of success, although the overall level of its achievements in this regard has arguably been more modest than what the party anticipated some twenty years ago.

In parallel with this decades-long active history, the ARF also became the foremost publisher in Armenian life of various genres of political literature—theory-related, policy-outline, propaganda, and history. The existing literature by and on the ARF far exceeds that related to the Hunchakians and Ramkavars. (Because of the very different circumstances in which it was published, literature by and on the Communist Party in Armenia is not included in this comparison.) Therefore, there is more accumulated positive historical knowledge on the ARF both at the scholarly and popular levels than about its traditional Diasporan rivals.

Most of the published primary and secondary historical literature on the ARF is in Armenian. Very little of what has been published in other languages (English included) has made original contributions to our academic understanding of the party’s history. Houri Berberian’s Armenians and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1911 (2001) and Dikran M. Kaligian’s Armenian Organization and Ideology under Ottoman Rule, 1908-1914 (2009) are rare, but welcome exception to this pattern, and I wish to see their contents become available to Armenian-reading audiences in some form in the near future.

* * *

However, this relatively vast historical literature on the ARF is extremely imbalanced as regards the different epochs of the party’s history which it covers. The overwhelming majority of collections of documents and secondary literature published by the party, its leaders and intellectuals—what we will call the “authorized” corpus of ARF literature—deals with the first 35 years of its history: from its founding in 1890 to the convening of the party’s 10th General Meeting in 1924-25, the first after the collapse of the ARF-led independent Republic of Armenia (1918-1920).

This was indeed an eventful period in modern Armenian history, and many professional or self-styled historians outside the ARF’s immediate circle of influence have also written extensively on the party’s involvement in these events.

Compared with the post-1924 period, which I will discuss next, today we have what I will describe as a satisfactory level of knowledge about what happened during this era and how the ARF both reacted to and partly shaped its important events. Polemics persist and sometimes they still get sharp, but these are more common among publicists and laypeople, who like to resort to selective historical facts or interpretations to make a point or to show their pre-existing sympathies for or against the ARF. There is, on the other hand, converging consensus among most professional historians when presenting conclusions on the most pivotal events of this period and the ARF’s involvement in the latter.

The increasing freedom enjoyed by historians in Armenia since the collapse of the Soviet system and the wider access which they now have to archival materials housed in various institutions in Yerevan have helped us find out more about certain aspects of the Armenian national-liberation struggle in the Ottoman Empire and even more about the period of Armenian independence (1918-1920). There have been few radical departures, however, from established interpretations, and many of the past arguments and counter-arguments within this context are being mostly reiterated, simply re-enforced through the use of some previously untapped primary sources.

The eventual unfettered opening of the ARF’s Central Archives, now housed in Watertown, Mass., may shed additional light on this period. However, it is highly unlikely that access to these papers, at present closed to most historians, will radically alter the way we now look back on this period.

* * *

This situation changes radically when we move to the post-1924 period of the history of the ARF, i.e. the party’s last 85 years.

For this period, not only do historians not have access to the party’s own archives (this is already an obstacle to those who are studying the ARF’s first 35 years), but, in this case, they are also told that the archives for this particular era are not only out of bounds because of an administrative decision, but that they are still poorly organized, if at all.

Moreover, unlike the previous period, the party itself has not undertaken any real effort to publish collections of primary documents pertaining to developments after 1924.

I find more curious the fact that ARF leaders have themselves been reluctant to pen their memoirs of this period. Famous ARF figures, who were active both before and long after 1924, rarely touched on post-1924 developments in their voluminous writings of autobiographical nature. Ruben Ter Minasian, Simon Vratzian, Vahan Papazian and Garo Sasuni are prominent examples of this group. Among members of roughly the same generation, it seems that Vahan Navasardian, Dro, Kapriel Lazian and Gabriel Lazian never wrote memoirs. The next two generations of ARF leaders, Gobernig Tandurdjian Adour Kabakian, Papken Papazian, and Hratch Dasnabedian, also have no published autobiographies. The only member of the ARF Bureau in the post-1924 period, who, to my knowledge, has published his memoirs, is Antranig Ourfalian. One may also add publications by A. Amurian, Misak Torlakian, S. Saruni, Armen Sevan (Hovhannes Devedjian), Baghdik Minasian, Melkon Eblighatian, and Suren Antoyan, but this is, I think, as far as one can go.

Some information on inner dealings within the ARF during this period can be gleaned from the autobiographical insights in the mostly polemical works penned by ARF figures, who left the party or were expelled at various times and under different circumstances. Within this group, we can mention Shahan Natalie, Krikor Merdjanoff, Khosrov Tutundjian, and Antranig Dzarougian.

Under these circumstances, the ARF press remains the major source to write about certain aspects of the party’s post-1924 history, especially the evolution of its ideology, priorities, and tactics.

However, the very limited access to archival sources and the dearth of published autobiographies are probably not the only reasons which have hindered conducting in-depth studies in the post-1924 history of the ARF. It also appears that there has also never been a sustained interest among the party’s leaders to sponsor such studies, as well as related public debates and discussions. The prevailing cautious attitude among contemporary Armenian Diasporan elites of all political persuasions toward openly tackling the nation’s recent history has also not helped.

It is very difficult to mention any published, high-quality, professional study which deals with any aspect of the party’s history in the post-1924 period. The book version of Gaïdz Minassian’s Guerres et terrorisme arméniens 1972-1998 (2002) unfortunately lacked the necessary scholarly citations so as to impose a public discussion among scholars at least around the various interesting issues that it raised. There have been very few PhD dissertations – e.g. those by Ara Caprielian (1975), Hratch Bedoyan (1978), and Nikola B. Schahgaldian (1979) – but they remain for the most part unpublished and are now probably also to some extent dated. Indeed, Schahgaldian and Bedoyan have been among the lucky few who have had the opportunity to consult archival material in the party’s possession. Shogher (Shoghik) Ashekian has also enjoyed that rare privilege when conducting research for her dissertation at Yerevan State University on the ARF and activities related to what is now widely described as the Armenian Cause in Lebanon in the 1960s and 1970s. However, recent biographers of famous ARF figures like Dro, Garo Sasuni, Avetik Sahakian and Ruben Ter Minasian continue to concentrate for the most part on their pre-1924 activities. They only devote a few pages to their activities in the ensuing decades. Indeed, Sasuni’s biographer, who did not have access to archival material in the party’s possession, openly admits that he could not find out the exact date when Sasuni re-joined the ARF Bureau!

This lack of adequate interest in post-1924 developments is probably behind another feature – the fact that Soviet Armenian and foreign (i.e. US, British, French, and other) archives, which can provide some glimpses on the post-1924 history of the ARF, also remain largely untapped by historians.

Historians in post-Soviet Armenia have also shown no particular interest in the post-1924 history of the ARF, which mostly occurred, after all, in the Diaspora. A collection of documents compiled by Vladimir Ghazakhetsyan, H.H. Dashnaktsutyune ev khorhrdayin ishkhanutyune, published by the ARF Bureau in Yerevan in 1999, covers mostly the 1920s period and only to some extent the 1930s; it is certainly a commendable exception. Eduard Abrahamyan, a young scholar, has recently written about ARF groups which clandestinely breached the Soviet border in the 1920s and 1930s. Nevertheless, it is obvious that, in both cases, the purely Diasporan component of the ARF’s post-1924 history is largely missing.

The absence of high-quality secondary literature makes it very difficult to provide informed opinion on many important issues which remain indispensible to evaluate the ARF’s post-1924 history as a whole: the party’s role in community-building in the post-Genocide Diasporan communities; its individual or group responsibility for the persistence of intra-party rivalries in the Armenian Diaspora; the related issue of the ARF’s involvement in Armenian Church politics; the ARF’s relations with Georgian and Azerbaijani exiles in the inter-war period; the participation of the ARF in electoral politics primarily in Lebanon, but also in Iran, Cyprus, and Syria; the gradual détente between the ARF and the Communist authorities in Soviet Armenia from the 1960s onward; and the party’s clandestine attempts to disseminate nationalist literature among intellectuals and the youth in Soviet Armenia, particularly from the 1970s. I will end this partial list of examples with a topic, which has intrigued me in the past few years: the gradual evolution from the 1960s of the ARF’s ideology from that of a “Cold Warrior” party, allied to right-wingers, to something more akin to a Third Worldist party at present, as well as the various manifestations of this gradual, but steady shift in the various host-countries where Diasporan Armenians live in significant numbers.

In the absence of good scholarship, polemics among those who hold pro- or anti-ARF views remain more acute when we encounter particular, usually violent, episodes of which the ARF was or is believed to be part. Examples include the assassination of Archbishop Ghevond (Leon) Tourian in New York in 1933; the cooperation of some prominent ARF figures with the Nazis during the Second World War; Dro’s post-World War II political and quasi-military activism in the Arab world; the discovery of armed caches and the subsequent arrest and trial of many ARF members in Syria in 1961-1962; and, finally, the occasionally bloody encounters between the ARF and the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) in Lebanon in the early 1980s. While each of these episodes can be treated as a thriller in its own right, a more in-depth and dispassionate study for each of them is necessary not only to cool down passions inherited from those who were participants in or contemporaries to these events but also as a means to better understand the party’s political and ideological evolution in the Diaspora, in parallel with the broader issues listed above.

The ARF’s involvement in political events leading to and since the outbreak of the Karabagh Movement in Armenia in February 1988 are perhaps too fresh to be analyzed in depth by professional historians today, but will undoubtedly concern them in the future. However, just as the current generation of historians complains about the above-listed and other difficulties when tackling the ARF’s post-1924 history, later generations of historians will probably also complain in similar vein about lack of encouragement to discuss and inaccessibility of primary sources pertaining to the post-1988 era, unless there is a radical change among the Armenian elites’ readiness to face contemporary history head on and an attendant change within the ARF ranks toward providing access to its archival material for professional historians without distinction of nationality or political convictions.

On the occasion of the 120th anniversary, I thank the ARF Central Committee of the Eastern United States for providing me with this opportunity to share my concerns during this public forum. I express the wish that the ARF leadership go back to its coffers, look for, and release unpublished memoirs that touch upon the party’s post-1924 history; make its archives accessible to professional historians as quickly and as widely as possible; take a parallel initiative and publish significant of the more interesting and important documents in its possession; initiate an oral history project targeting party veterans with acknowledged intellectual depth; and, finally, encourage public debate on post-Genocide Diasporan and recent ARF history.

I believe that such endeavors will contribute to having an educated Armenian public which can make informed decisions on important matters in an elegant climate. Honestly, while I won’t rush to bet that such changes will occur in the foreseeable future, I promise to be among the first to cheer loud and clear whenever I see some progress in the direction that I have suggested today.

[1] This article is a slightly amended version of my paper presented at “The ARF at 120: A Critical Appreciation” Public Forum held in New York on Sunday, November 21, 2010. The author thanks the following colleagues for their comments on an earlier draft of this presentation: Aram Arkun, Bedross Der Matossian, Marc Mamigonian, Garabet K. Moumdjian, Garo Ohannessian, Razmik Panossian, and Khachig Tölölyan

ARF: Reflections and Refractions (1988-2010)

Below are the comments delivered by K.M. Kourken Sarkissian (President, Zoryan Institute) at the public forum titled “The ARF at 120: A Critical Appreciation,” held at the New York Hilton Hotel on Nov. 21, 2010.

Ladies and gentlemen,

Since I have been invited here as president of the Zoryan Institute, allow me to start with a brief word about the institute. It was founded by a small group of Armenians in 1982, absorbed with questions about their history, identity, and future as a nation. They concluded that there was a crucial need for a place to think critically about the Armenian reality. Intellectuals, scholars, and the community at large would raise substantial questions about contemporary Armenian history and identity, and help develop new perspectives on vital issues, both current and future. Its primary goals would be for the Armenian people to express their history in their own voice; to understand the forces and factors that shape the Armenian reality today; and in doing so, to engage the community in a higher level of discourse, but without claiming that it had all the answers.

It is from this perspective that I will attempt to reflect on the ARF’s role in the diaspora and Armenia for the past 22 years, since the beginning of the Karabagh movement. Because of time constraints, I will present an abbreviated analysis using only selected examples. Hopefully, we can get into more detail during the Question & Answer session.

To start with, I will give a little background on my experiences with the ARF. I attended ARF schools, where we learned not only about Armenian history and geography, math, and science, but also read Roubeni Housher, Zartonk, and about the lives of Christapor, Simon Zavarian, Stepan Zoryan, and what their work meant for the nation.

As part of our education, we learned from the voluminous Hayastani Hanrabedoutiun by Simon Vratzian, the last prime minister of the Armenian Republic, how the first republic was established, the spirit in which the constitution was developed, the challenges that the young country faced, the importance of democracy, and the participation of other political parties, women, and minorities in the Armenian Parliament. Running throughout our education was the genocide and the demand for its affirmation and justice. A free, independent, and united Armenia was equally emphasized. The ARF was successful in indoctrinating the youth with the importance of civic engagement and inspiring them with the literature to which I just referred.

In the diaspora, the ARF was visible in all aspects of Armenian society, in the social, political, economic, religious, cultural, and educational spheres and, last but not least, in sports. They created a sense of community through their centers, provided a place for everyone, from youth to the elderly, and promoted Armenian history and identity.

When I came to the U.S. for my university education, I lived in California, where I worked as a volunteer translator for the Asbarez newspaper. As a university student living in the U.S. in the 1970’s, I was inescapably confronted by the discord over the war in Vietnam. We learned about how the government was misrepresenting to the people what was happening in the war. The youth began questioning authority and the legitimacy of the government and its agencies. A true social revolution was taking place. Naturally, Armenian youth also began to question the authority of their own leaders, whether of the church or the political parties. Unfortunately, it soon became clear that these traditional institutions were dedicated to keeping the status quo. While I had grown up with the ideals and principles of an organization that was to be decentralized and governed from the bottom up, I eventually realized that the ARF had actually become highly centralized and was run from the top down. Furthermore, it had developed an institutional attitude towards individuals and other organizations that could be summed up as “if you are not with me, you are against me.” The fact that the ARF had drifted from its original principles led to great disappointment and disillusionment, not only for me, but also others.

With this background, let me now turn to events that took everyone by surprise and resulted in important opportunities missed by the ARF and almost all Armenian Diaspora organizations. In the mid-1980’s, Mikhail Gorbachev announced new policies of perestroika, meaning restructuring, and glasnost, meaning openness. The relaxation of censorship and attempts to create more political openness had the unintended effect of re-awakening suppressed nationalist feelings throughout the Soviet republics. The Karabagh movement was one of the first efforts by a Soviet people to test these new policies.

On Feb. 20, 1988, Nagorno-Karabagh, conscious of the complete depopulation of Armenians from Nakhichevan and the trend towards the same in Karabagh due to the policies of the rulers of Azerbaijan, passed a resolution calling for unification with the Armenian SSR. Protests quickly developed into a hugely popular mass movement, with an estimated 1 million people filling the streets of Yerevan during the last week of February, listening to speeches and shouting “Gha-ra-bagh! Gha-ra-bagh!” Peaceful protests in Yerevan supporting the Karabagh Armenians were met with anti-Armenian pogroms in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait.

Gorbachev’s inability to solve the Armenians’ problems created dissatisfaction and only fed a growing hunger for independence among the Armenians. Clashes soon broke out between Soviet Internal Security Forces (the MVD) based in Yerevan and Armenians who decided to commemorate the establishment of the 1918 Republic of Armenia. The violence resulted in the deaths of five Armenians. Witnesses claimed that the MVD had used excessive force and that they had instigated the fighting. Further firefights between Armenians and Soviet troops occurred in Sovetashen, near the capital, and resulted in the deaths of some 26 people, mostly Armenians. The actions of these people responding to glasnost emanated in practice from a right asserted from below, a philosophy that the ARF had taught in its institutions.

It was surprising, therefore, that the response of the ARF to this movement was to issue a joint statement with the Hnchak and Ramgavar Parties which, while pledging their support for bringing Karabagh within Soviet Armenia, concluded as follows:

“We […] call upon our valiant brethren in Armenia and Karabagh to forgo such extreme acts as work stoppages, student strikes, and some radical calls and expressions that unsettle law and order in public life in the homeland that subject economic, productive, educational, and cultural life to heavy losses; that [harm seriously] the good standing of our nation in its relations with the higher Soviet bodies and other Soviet republics.”

Naturally, coming especially from the ARF, which embodied the national liberation movement, this was not well received by the people in Armenia and Karabagh, nor the leaders of the Karabagh movement. This was especially true after the pogroms against Armenians in Sumgait, Kirovabad, and Baku. Some within the ARF felt this appeal to not upset the status quo was a betrayal of the revolutionary ideals of the party and its principle of struggling for freedom and independence. Others went as far as accusing the ARF of not wanting the success of a movement over which the party itself did not have control.

People started to question the role that diasporan political parties could assume in an independent Armenia. What should be the role of a party based outside of Armenia? Could a diasporan political party act against the interests of the government of the homeland without also acting inadvertently against the interests of its people? While the ARF had filled its supporters with a spirit of engagement and activism, it shook their faith by demonstrating its aversion to change and supporting the status quo.

Just around this time, we, too, at the Zoryan Institute had a relevant experience with the ARF. Some of the founders and early volunteers of the institute had, like me, grown up within party institutions, but had made a conscious decision to establish Zoryan as an institute completely independent of any of the traditional community organizations. In March 1988, the party’s top leadership in Athens demanded to have its representatives form the majority on the institute’s Board of Directors. Naturally, this was not acceptable to our Board, which was made up of scholars, including non-Armenians. The party then issued an order to all of its members on April 1, 1988, to withhold support from the Zoryan Institute, with the threat of disciplinary action, including dismissal from the party. Fortunately, with credit to the new leadership of the ARF, this decision was reversed some 18 years later, and we now enjoy cordial cooperation with the ARF, as with all organizations.

Going back to the Karabagh movement and Armenia’s independence, the ARF, being severed from Armenia, did not play an active role and was in essence an outside observer of the events, as were most of the diasporan organizations. Nevertheless, it disapproved of almost everything done by the Armenian leadership and the Hayots Hamazgain Sharzhum (HHSh). The ARF stayed away from the celebrations held in the Armenian Parliament when the referendum to break away from the Soviet Union passed with an overwhelming Yes vote. The ARF felt that it had the legacy, the political experience, and the right to govern. During the presidential elections, it anticipated that, based on its historical record, the people of Armenia would welcome the party with open arms and sweep it into power. Instead, Levon Ter-Petrosian won the election with 83 percent of the vote. This was only to be expected. The Karabagh movement was innate in Armenia, understood the people, the power bases, and the local social and political dynamics.

From the outset, the ARF leadership did not hesitate to reprimand and rebuke the Armenian government for its actions. In an interview, the chairman of the ARF described the rulers of Armenia as just adolescent children in international politics, pointing to the ARF’s 100 years of political experience. Even before Armenia declared its independence in September 1991, and Levon Ter-Petrosian was elected president in October, the Dashnak Party’s official organs, such as “Troshag,” were vilifying him with the worst sarcasm and innuendo in their pages.

Actually, when the ARF registered as a political party in Armenia, it did not allow itself the time to earn the confidence of the people. Time was needed to integrate with the power centers of the country, such as the army, the rapidly emerging private sector, cultural institutions, and the church before running a candidate for the presidency. Instead, the ARF simply relied, once again, on its historical legacy, and used its leverage from the diaspora, in terms of financial and human resources. To offset the ARF’s leverage, the Ter-Petrosian government, as governments will always do, used other diasporan organizations, such as the AGBU, other traditional political parties, and particularly the Armenian Assembly, as their liaison with the diaspora and a counter-balance to the ARF’s influence in the U.S., where the ARF was best organized. Levon Ter-Petrosian even appointed a protégé of the Armenian Assembly, Raffi Hovannisian, as his very first foreign minister for several reasons, one of which was to help reduce the influence of the ARF in Armenia and the diaspora.

President Ter-Petrosian was so bitter towards the ARF that in a famous television speech on Dec. 28, 1994, unfairly banned the party, claiming evidence of a plot hatched by the ARF to engage in terrorism against his administration, endanger Armenia’s national security, and overthrow the government. He not only shut the party down in Armenia, jailing a number of its members, but also had the ARF declared as a terrorist group in other countries, affecting the freedom of movement of the ARF’s leading members.

One wonders how things might have turned out had the ARF and the HHSh taken the opportunity to reevaluate the historical moment and their roles at this critical juncture, and see if they could have worked together, rather than attack each other.

During the 1996 presidential election, the ARF protested loudly the government’s violence against the opposition, the beating of opposition parliamentary deputies, the shutting down of opposition party headquarters, and the sending of tanks and troops into the capital. Within days of Robert Kocharian becoming president in 1998, however, the ARF was rehabilitated.

The Oct. 27, 1999 assassinations in parliament caused a major crisis in the country. The Republican Party and the Yergrabah movement, led by Vazken Sarkisyan, who was now assassinated, engaged in self-destructive political infighting. The People’s Party (Demirchyan’s party) split into two. The political situation was in turmoil. Prime Minister Antranig Markaryan stepped forward to put the interests of the country ahead of his party and put together a coalition, as Kocharian himself did not belong to a political party. In this chaotic scenario, the ARF, as a newcomer, became a viable alternative, as it filled an ideological void within the political spectrum and slowly gained momentum. The party claimed it was in the coalition to change the system from within, and people believed it. The ARF had some initial successes. It established its infrastructure as a political party, with offices, administrative and political staff, media outlets, and Hai Tahd activities, and it also began the process of moving its Bureau headquarters to Armenia.

The ARF entered parliament in 1999 and joined the ruling coalition in 2003. In 2007 again, its members assumed ministries, including Agriculture, Education and Science, Labor and Social Affairs, and Healthcare. These were critical areas that could have used some of the leverage that the ARF has in the diaspora to benefit Armenia, but in the long term, resulted in a lost opportunity.

In 2008, the ARF joined a coalition with the Serge Sarkisian government, despite the March 1, 2008 presidential election fiasco, when there were voting irregularities, beatings, arrests, a 20-day state of emergency leaving some 10 people dead and hundreds wounded, and a crackdown on civil and political rights throughout the year, whereby freedom of assembly and expression were heavily restricted, and with opposition and human rights activists imprisoned, where many still remain today. In spite of all this, the ARF remained a silent bystander, if not a participant, by association.

There was certainly a lot to protest under both the Kocharian and Sarkisian administrations, as reported by such reputable organizations as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and the World Economic Forum, to name only a few.

These are just some of the serious threats and challenges to the country, as well as to any Armenian political party hoping to serve the country: Arbitrary use of the rule of law, or lack thereof, and selective protection of private property. Concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. Oligarchs controlling imports and key sectors of the economy for their personal benefit, creating a huge gap between them and the majority of the people, who live below the poverty line. Unemployment and reliance on external resources. Rampant government corruption. Use of government for partisan purposes. Government control over electoral process, minimizing the role of the electorate and perpetuating an elitist, non-responsive party system. Concentration of political power in the hands of a few. Political prisoners, intimidation, beatings, killings. Political censorship of media. Demographic decline. People, especially the youth and those with saleable skills, leaving the country in droves. Lack of youth inhibits conscription for Armed Services.

The ARF has certainly demonstrated its ability to successfully mobilize the masses to protest forcefully in communities around the world, when the need is there. Unfortunately, the ARF’s criticism of the Kocharian and Sarkisian government regarding the failures and/or threats listed above was only minimal at best, in stark contrast with their strong criticism of the Ter-Petrosian Administration, which was also corrupt, as well as of the Sarkisian government during the protocols. This raises serious questions. Was its silence in the face of all these threats and injustices the price that the ARF was willing to pay just for being part of the government? Was being in government more important than being true to the ARF’s core principles? What material benefits did the ARF achieve for the people of Armenia as part of the coalition for 10 years, when the situation in Armenia, as described above, is now worse than ever?

Finally, in April 2009, the ARF left the coalition, due to its opposition to the Turkish-Armenian protocols. However, this occurred only after April 24, the 95th anniversary commemoration of the genocide, by which time President Obama had made his declaration that he would not interfere with a genocide resolution, as the parties were negotiating.

Undoubtedly, the ARF is searching for its place and role, now that it’s out of the government. Unfortunately, the ARF’s participation in the coalition still taints its moral authority, for the time being. However, being out of the coalition liberates the party and gives it the opportunity to change its modus operandi, refracting completely in a new direction. The ARF should now come up with a clear vision for the future of Armenia, or be part of a group that does, and promote that vision through its well-organized structures in the diaspora and Armenia. In doing so, the party may even provide constructive criticism of government policy, should the latter fail to realize that vision.

History has shown that the ARF works best when it follows its grassroots, bottom up, decentralized principles. What does that mean today? If the ARF is to be truly a decentralized party, then it should serve its local constituency and be accountable only to them, as no country should tolerate any political party that draws its ideology and resources from abroad.